This article is excerpted from Hands & Minds: A Guide to Project-Based Learning for Teachers by Teachers, and published here with minor edits.

In an ideal vision of project-based learning, the project comes to life because students feel an authentic need to master thoughtfully selected learning goals in their quest to create meaningful and beautiful work.

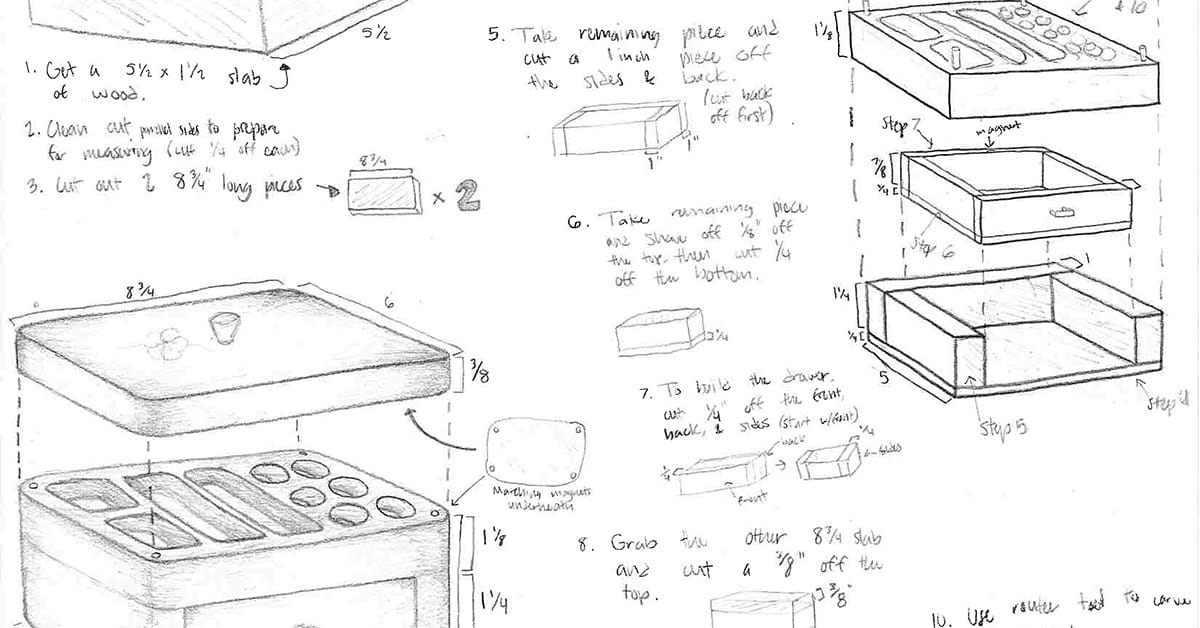

If a teacher starts planning a project with an idea for a product, showcase event or performance, or other end result in mind, it’s a good idea to make a prototype as soon as possible—and to reverse engineer it to understand the learning goals inherent in its creation.

But if a teacher begins planning by first naming what the students should learn, coming up with the end product or exhibition event takes some more thinking. I was in this situation when I decided to do a project in which students gained an in-depth understanding of the Syrian refugee crisis, and again the following year when I wanted students to learn to assess the credibility of news sources. In both instances, the learning goal preceded the product, and as a result, I had to create prototypes of multiple products until I found the one that worked well for my students, our resources, and my strengths as a teacher.

In the cases where teachers have a learning goal, but no product, they might ask themselves the following questions.

In what professions would you need to gain expertise in this?

Any valuable learning goal will have application in the adult world outside school. Therefore, a good first step to coming up with a meaningful product is to think about the professions where this learning goal is relevant.

At Morro Bay High School, teachers were excited to teach students about the people, geography and economy of the local agricultural community in San Luis Obispo.

Professionals who would likely work on a project like this include:

What projects would a professional do?

Now that you have a list of professions that use this type of knowledge, brainstorm the products that these professionals would make in order to share their learning.

What are the teachers—and students—most excited about making?

Do you dream of being a documentary filmmaker? Are you passionate about supporting a local issue or solving a problem in your community? How about a rocket scientist? Now is the time to connect with your own passions outside of the classroom in order to decide how to harness this energy into a project.

When you have an idea, buy some snacks and invite students to come to your room during lunch to talk about the next project. This way, you can informally share your idea and get their responses. You will probably end this lunch meeting with a better idea than you started with.

When you are ready—when you have taken steps to plan what you can, but still have important questions about what students might create, how it might be displayed or how it might be assessed—convene a group of students and/or colleagues for a Tuning Protocol.3

In the case described above, the teachers at Morro Bay High School consulted with students and decided to create a field guide to the agricultural community surrounding their school. The teachers and students agreed that they could be creative, have fun, do valuable original research and showcase their community, and stay true to the essence of the English class that took the lead on the project, by focusing their learning towards the creation of an original book documenting the local agricultural community.