This article is excerpted from Hands & Minds: A Guide to Project-Based Learning for Teachers by Teachers, and published here with minor edits.

“True reflection leads to action. On the other hand, when the situation calls for action, that action will constitute an authentic praxis only if its consequences become the object of critical reflection.”

—Paolo Freire

Self-understanding is one of the oldest and most venerated forms of wisdom; but it does not come easily. A figure no less than Socrates made it his lifelong quest and only managed to succeed in knowing what he did not know. When the Delphic Oracle implores us to “know thyself” or when Socrates informs us that the “unexamined life is not worth living,” they are making the case for reflective learning as a lifelong process which is grounded in experience. For Socrates, this experience primarily involved dialectical conversations about the nature of truth, beauty, and virtue. For John Dewey in the twentieth century, it involved connecting personal experience to a larger educational and civic context. For both, reflection is the essential ingredient for life-long learning and personal growth. It transforms individual raw experience into personal meaning and collective value.

Reflection occurs when students and teachers think about what they are doing, why they are doing it, and what they have learned. It is the linchpin of project-based learning (PBL). At its most advanced, it is not simply the mind noticing what the hands are doing; it is a metacognitive endeavour of learning how the hands and mind work together and inform one another.

Metacognition is thinking about thinking with the aim of improving learning.1 It occurs when a person evaluates his or her thinking and takes steps to understand and improve his or her thought patterns. A student who turns off her computer because she realizes that she is distracted by it, thinks metacognitively, as does a reader who can’t understand a dense paragraph and consciously employs reading strategies to work through it.

Reflection is the pause in activity that allows students to think metacognitively and to make connections to other experiences and to evaluate what they learned. As recent neuroscience has shown, such pauses are essential for learning; in the words of Mary Helen Immordino-Yang, “rest is not idleness.” Taking a moment to reflect or event to simply rest increases the overall effectiveness of brain processing.3 Similarly, planning for reflective opportunities at key moments in the curriculum allows for the “active retrieval” of past knowledge that assists in retention and creative thinking.

As opposed to “one size fits all” assessments that often leave students behind, reflection promotes equitable access to deeper learning opportunities and outcomes. Facilitating structured time and space for individuals to think about their own thinking provides a diverse range of students with the opportunity to draw personal connections to the project, determine its relevance for their lives, and assess their individual strengths and challenges.

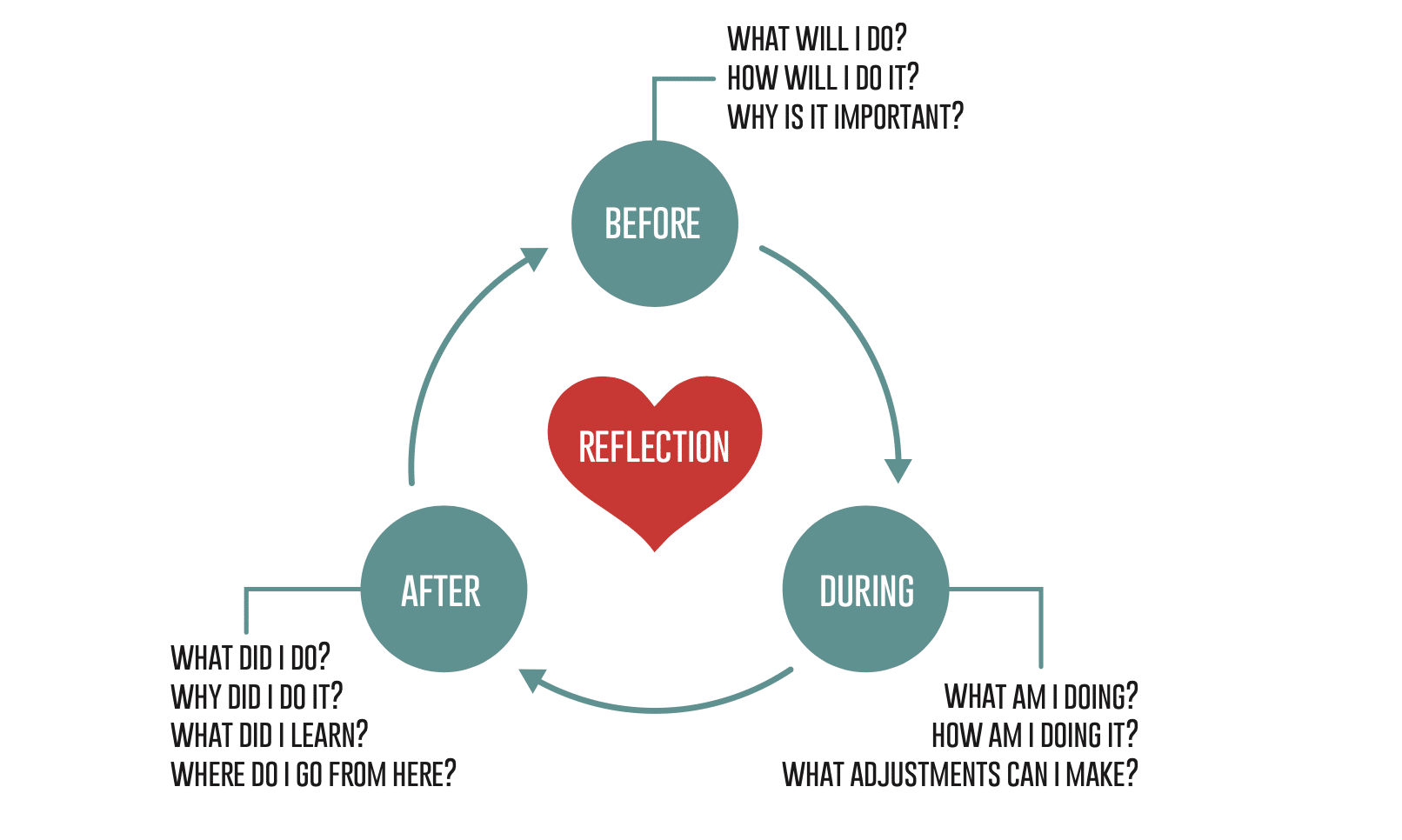

Education involves a process of becoming—in the present we reflect on our past in order to project ourselves into the future. In PBL we can apply this principle by planning for reflection before, during, and after specific project components. These types of reflections can take the following forms:

The following offer prime opportunities for reflection at HTH and other schools that engage in PBL:

Students can reflect in writing that is shared with the teacher, students, the public, or is kept private. Common written forms of reflection:

Students can reflect through small or large group discussion. Common forms of dialogic reflection structures:

Teachers can reflect with their students by:

Reflection can also be “small” or “big” in nature. “Small reflection” is short, quick, and frequently impromptu. “Big reflection” is planned carefully and often part of the finished product, or during specific time set aside during key steps in the process of creating a project. While big reflection necessitates planning, using small reflection necessitates spontaneity. Big reflection requires teachers to plan for reflection like any other component of their project: teachers will want to consider how their project is mapped out and where students could most benefit from moments of analyzing their own thoughts. Small reflection, on the other hand, calls for teachers to be aware of moments, sometimes critical ones in projects, when students will benefit from the time to analyze, critique, or thoughtfully evaluate what is happening then and there.

Small reflection is helpful in the following circumstances:

Working with students can, at any point, require moments to slow down and think about things. It is helpful to have a set of “Go-to” reflective questions or prompts ready for a variety of situations. These questions are effective when students need to self assess and to take a moment for reflection:

Teachers need to know where students are in their understanding. What did students “get” from a learning experience, and what do they “need” to keep making progress? Knowing when to move on or when the topic is difficult requires reflection for understanding to occur; “Gots and Needs” questions can help.

Big reflection is helpful in the following circumstances:

Many schools will keep portfolios (collections of student work) which allow students to select, keep, organize, and analyze samples of their work as evidence of their learning over long periods of time. Through reflection, this work can be used to help students understand their thought patterns and processes, and understand their growth.

Reflective questions can also be used to facilitate group work. Before student groups commence working, teachers should ask the group members to collectively determine their goals for the day, or even ask for a group leader or project manager to set goals and share them with his or her partners. Individuals within those groups should then set a plan for how they will help the group accomplish those goals. Teachers and students should set check in points—perhaps half-way through a class period, or at the end of specified amount of time, for teachers to prompt groups to pause and reflect on the progress they have made in the project. This will help the group determine whether it needs to continue or change course and do things differently. Keeping track of these reflections along with student work samples helps students clearly articulate how they did their work, how they made important decisions, how they communicated within the group, and what their thoughts are about these experiences.

These questions are effective in the course of group projects:

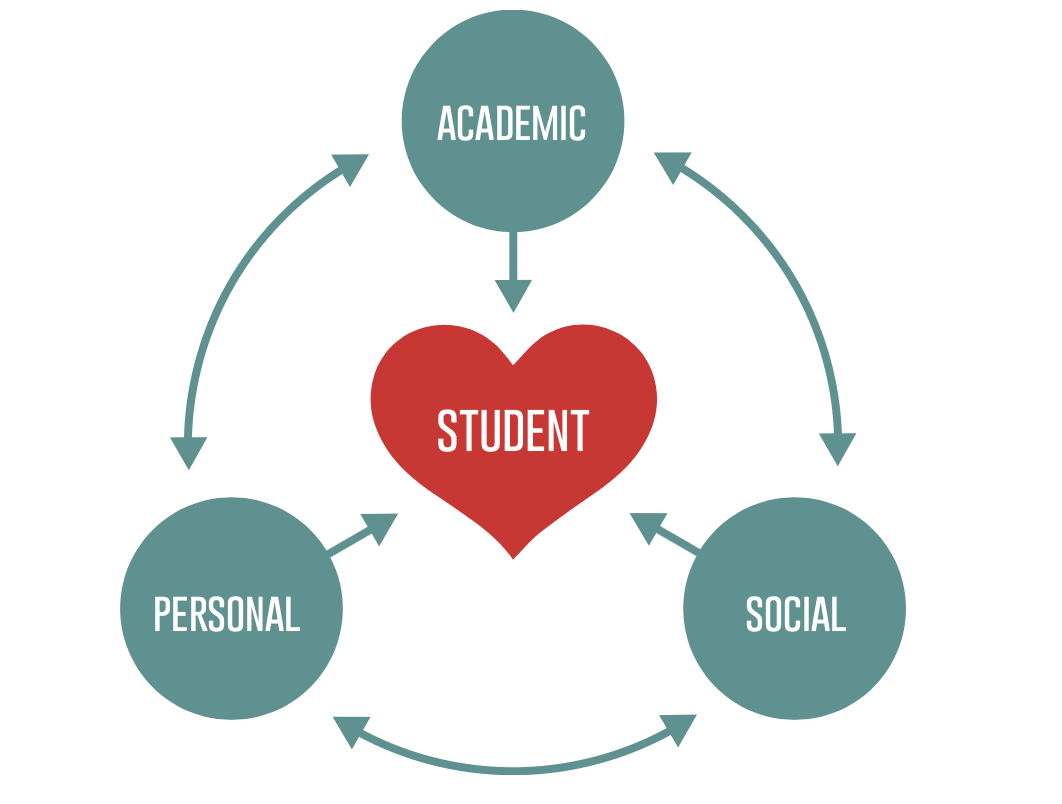

Students, like all people, learn by reflecting on experience. School and classroom experience coalesces around three experience types: academic, personal, and social. Each experience type interacts, complementarily or not, with the other. In rich experiences, such as in a well facilitated project, the three experience types are in full play, likely to dynamically inform each other in ways that result in deeper learning.

The three experience types are not discrete entities. But by focusing on each, teachers can see the role each has in bringing learning to its fullest potential. If the teacher feels one aspect of experience type is lacking in importance, he or she can give weight to it by making changes to the project. In addition, through the systematic use of reflective practices, students come to realize the importance of the connection between their academic, personal, and social selves.

The three experience types are not discrete entities. But by focusing on each, teachers can see the role each has in bringing learning to its fullest potential. If the teacher feels one aspect of experience type is lacking in importance, he or she can give weight to it by making changes to the project. In addition, through the systematic use of reflective practices, students come to realize the importance of the connection between their academic, personal, and social selves.

PBL environments are rich in a variety of academic experiences—reading, writing, numeracy, critical thinking, problem solving, design, critique, and presentation. Academic reflections attempt to answer the following questions:

Upcycling refers to the reuse of discarded objects or material to make a higher quality product. In “The Upcycle,” Pat Holder and David Berggren’s eleventh grade students approached local non-profit organizations to determine their material needs and designed a product out of upcycled materials that met those needs. Small groups of students built products such as glider launchers, outdoor wash basins, and toy race car ramps, and the students documented their progress, interactions, and thoughts along the way. They published a book chronicling the building, drafts, process notes, and reflections—the foremost being their reflections on academic problem-solving that it took to make the products.

Students and teachers confronted three reflective essential questions:

The Upcycle project incorporates practices of big reflection—reflective opportunities are planned as part of the curriculum, implemented throughout the project, and made into a final product devoted to reasoned, deliberate, and contemplative problem solving. Additionally, it demonstrates the interconnectedness of experiences: while the reflective opportunities published in the students’ book are generally about academic experiences related to engineering and the humanities, the project itself also included significant personal and social components.

Before building their products, students needed to discover the needs of the local non-profits that would be their real-world clients. To this end, in groups of three, students visited a local non-profit, learned more about its mission, and interviewed interested parties. One student group worked with the San Diego Air and Space Museum. They discovered that the education department needed to replace its old glider launchers. Students worked on three different launcher designs and weighed the pros and cons of each before finalizing one. At this point—before the design and build cycles —students wrote answers to the following questions and saved their writing for later publication in The UpCycle Book:

In the Upcycle Project, this stage of the process involved building the product and maintaining dialogue with the client to ensure that their needs were being met. Students used a variety of tools, including band saws, welding machines, and drill mills, but they did not just use their hands—they regularly paused to think through potential solutions to unforeseen engineering difficulties, they used restorative practices to resolve interpersonal conflicts inside of groups, and they debated solutions to philosophical and social questions raised by their work. Students answered the following questions:

After the products were completed and delivered to clients, students put the finishing touches on The Upcycle book— writing of which had started in the “during stage” of the project. At this point, students could now look back on their previous entries to develop their reflections. In addition to these, students also collected design plans, process steps, sketches, and photos to complete the book.

Students were asked to reflect on the following questions:

During this stage of the project, when Pat notices that students are getting stuck or frustrated he will often instruct them to go on a “walk and talk.” Students go for a walk around the building to discuss their challenge and return with possible solutions. Pat is deliberate to do two things: remove the student from the environment of the problem to give him or her time and space to think (and to remove the class as a potential audience so students can communicate thoughts honestly), and to free the mind to think by getting the body up and moving.

The Upcycle project contained a heavy academic component—reading about environmental problems and debating their impact on humanity, learning how to design and build as an engineer, and writing an interdisciplinary book—while also interacting with students’ personal and social experience. For example, students solved problems in social groups, and learned that academic problems can have social solutions. Or, when students saw the social significance of their engineering product, their work became more meaningful for them personally. It was not just an academic exercise, but a project for a real-word client with a larger social and environmental significance. When students reflected on their experience meeting clients, they saw how their personal choices and experiences inform their academic work. The Upcycle project required the integration of academic, social, and personal experiences, and in so doing, made itself meaningful to the students. The Upcycle project benefits from the relationship between small and big reflection. Big reflection occurred in key moments planned by the teachers to align with transitional points in the project, and because The Upcycle book required publishable reflective writing. To complement the planned big reflective milestones, teachers took advantage of serendipitous moments and used small reflection organically. Groups of students analyzed their own thinking as needed by the demands of the project or when tension were on the rise for them. In times like these, teachers used a small reflection strategy by asking student to “walk and talk.”

Personal experience refers to the daily lived reality of individuals. For students, personal reflections can refer to large, existential concerns—who am I and where am I going? Or, it can focus on more practical things like personal thoughts about study skills or future goals. A fundamental aspect of schooling is helping students see how different parts of their life relate—how to “figure it all out.” Teaching students the interrelationship between their personal, academic, and social experiences is central to this process. By exposing students to a variety of people, situations, and academic endeavors—and providing them with engaging reflective opportunities—students learn that reflection is not just an academic exercise, but a tool for understanding life. Personal reflections often take the form of:

Imagine a class in which students partnered with several community organizations to record biographical stories of service from local veterans, and to contribute their stories, photography, and videography to local community centers and a museum. However, in this project, teachers knew that following the community partnership, they would launch a reflective writing project in which students wrote reflective autobiographies. These reflective autobiographies connect their community work with important qualities they value in themselves.

Many teachers assign various forms of autobiographies, and with good reason: telling a story of self is a vital step in understanding who one is, and has real value in the world beyond school. Stories of self help friends and family relate to one another and develop a sense of identity and community; sharing a compelling autobiographical statement is a fundamental leadership skill; and (perhaps most notable to high school students and teachers), personal statements are required writing for admission to nearly all four-year colleges and universities in the U.S.

The Reflective Autobiography can happen at any grade level, or any time in the year, but certain grades and times maximize the impact of personal reflection. For example, in the fall semester of twelfth grade, students write personal essays as part of a college application process—they are entering the adult world, and they are making a case for their place in it. In the fall semester of ninth grade, students write personal essays about their identity, their values, and their heroes—they are entering a new academic community, and they are reflecting on their identity as young people and students. In elementary and middle school, students write personal stories about their hopes and their fears, their family and their friends, their accomplishments and their goals for their lives—they are sharing their identity and considering their many places in the world.

Regardless of the specific grade level or even the name of the assignment, the Reflective Autobiography has common design features that leverage the power of metacognition, self-reflection, and even soul-searching. Like the Upcycle project, the Reflective Autobiography is a project that hinges on big reflection: reflective writing is baked into key elements of the project design.

Before writing a Reflective Autobiography, students spend a significant amount of structured time journaling and engaged in reflective discussion about their lives. They reminisce about the past and compare sometimes quite different approaches to life. Teachers should use rituals like a daily journal prompt followed by a pair-share session and then whole class discussion, to establish a safe space and classroom norms for personal reflection. These structured conversations help get the students ready to write. Getting started is often the most difficult part of the writing process—this is true of any kind of writing, but especially true for inward reflection.

Consider prompts such as:

As students explore their lives for fertile content, they will be inspired by high quality models. All students should read selected personal memoirs and write about vivid moments in their lives inspired by these texts. Provide at least one high quality model that fits well with your students’ comfort levels as readers and have each student bring in one sample of a reflective memoir that they respect as an example of a high quality autobiographical text—this can be a speech, poem, song, vignette, or anything similar. If the student examples are songs or anything similar, have them transcribe the words so that they can focus on the writer’s use of language.

During this stage of the project students write their essays. Each journal prompt and each discussion is the raw material—the drafts—needed for students to create one polished draft of a Reflective Autobiography. Situate the students during the writing process so that they can easily access their journals and at least one high quality example of professional or student work—the goal is the create an environment in which students consider their ideas in the context of the type of writing they are trying to create. If this project is done for eleventh or twelfth grade students, focus their writing towards the personal statements required for the Common Application and the University of California prompts. If this project is done in elementary school—or any other context—focus the students’ writing on relevant prompts such as “Who is a hero in your eyes, and how can you be a hero also?” or “Imagine yourself 10 years in the future—and write your autobiography.”

As students are engaged in the drafting, critique, and revision processes, periodically stop and direct students to write reflectively in their journals. Consider prompts such as:

Students’ final drafts are exhibited for an authentic audience such as:

Following the student exhibition, students look back at the work they have done and think about what they learned and how they learned. They write a reflective letter to the teacher that responds to prompts such as the following:

While The Upcycle project was driven by academic reflection, The Reflective Autobiography is driven by personal reflection. Students are equipped to successfully complete their personal essays because they work together to share and critique their ideas, and also because the stories are about themselves. Such participation demonstrates a fundamental paradox: developing a personal identity is social in nature. Students develop a keener sense of who they are by having their self-conceptions affirmed or challenged by their communities—their points of view become more refined as they are thoughtfully and respectfully questioned by others.

The Reflective Autobiography project does not stop there. Personal experiences influence social and academic experience; when students know themselves better, they better address the issues they face in the social world (“I’m going to be nervous, so I need to practice”). Self understanding has an impact on the academic world, as well. Much of academic success is based on non-cognitive factors such as academic self-perception or tenacity.6 Personal reflection develops through and informs positive academic and social experiences.

Social experiences can take many different forms. At the macro level they include institutions and socio-political forces that impact the daily lives of individuals. At the micro level they involve everyday interactions: family life, making a purchase, talking on the phone, or in this instance, the social interactions happening everyday in school and the classroom.

Socio-political experience refers to a student’s relationship to the local community, nation, or world. As Paulo Freire finds in The Pedagogy of the Oppressed, education should be personally and socially transformative. For this to happen, students must be equipped to reflect on the role of social institutions and how those institutions promote or hinder equality and justice. Likewise, students must additionally reflect on their own role in maintaining, ameliorating, or revolutionizing those institutions.

When students reflect on their own socio-political experience they become aware of the various contexts that enmesh their lives. They are subsequently empowered to take action, should they choose, on a variety of local and global issues. Reflection of this nature promotes equity and student voice. When teachers engage students with authentic socio-political reflection, students are empowered to reach their own conclusions.

Reflection of this sort takes the form of the following questions:

Walking through the campus of San Lorenzo High School during lunch on a Tuesday afternoon in the fall of 2016, the casual observer would witness scenes similar to those of many American high schools—students eating spicy hot Cheetos, drinking Monster energy drinks, and consuming various other assorted junk foods. But that same observer would have also seen something out of the ordinary—some students were eating homemade Kale chips, stovetop popcorn, and engaging in campus food activism: they tended to a food stand and sought signatures on a petition drive.

The nine San Lorenzo High School students who organized Kale Yeah! created this event as part of an extra-curricular internship sponsored by Project EAT—a program sponsored by the Alameda County Office of Education. Kale Yeah! was their way of raising awareness about healthy eating in order to persuade other students to sign a petition for the inclusion of a salad bar in the school cafeteria. Kate Casale, their Project EAT internship coordinator, taught them a method of community based research called Youth-Led Participatory Action. The guidelines: to identify major concerns in their schools and communities, conduct research, and propose a course of action—essential skills for any project related to the macro social experience.

Big reflection can develop organically out of students contemplating their social experience (in this case, the food culture of their school). Kale Yeah! works when teachers incorporate student voice and choice into the early stages of project design. Neither students nor teachers went into the project knowing its full shape or how they would share their learning with the community. The idea for a lunchtime food stand and cafeteria petition developed after extensive research, reflection, and student-teacher collaboration. It’s also a reminder that exhibitions of learning do not have to be singular events; they can be on-going like the food stand. Nor do exhibitions of learning have to be planned during initial project design, they can evolve as the logical action-to-be-taken arising from research and reflection.

The students who conducted this project believed that there was a problem with the food culture on campus. But what to do about it? Their first step was to develop the guiding question: “Would students make healthier choices if they had more information about the foods they were eating and had healthier options available to them?” Their next step was to map the community by making lunch time observations and conducting student focus groups. This research provided the basis for reflective opportunities which resulted in the formulation of an action plan.

Examples of focus group questions:

Examples of cafeteria observation questions:

In this stage, students started with analysis of their research and ended with action. They analyzed data, presented their findings, and made recommendations to the school’s ASB. This led student researchers to recommend a petition for a salad bar in the school cafeteria.

In another example, cafeteria observations revealed that students were misinformed or under informed about other food options on or near campus. This led to recommendations for changes in the cafeteria and for an educational campaign on campus. Students took their recommendations and asked, “How can we make this happen?” Questions that guided this stage of the project included:

Students created a post-project report that explained the process and included the results of student reflection. Students asked themselves questions that are common to good post-project reflections:

More specific questions related to the focus groups included:

Reflection without action is meaningless, but action without reflection may be worse. Not only did the students of Kale Yeah! conduct research and reflect on that research, they used their reflections to guide their project. It took courage and faith on the student’s part to start a project not knowing where it will go or could go. One could imagine a project like this where students conducted their focus groups, got their data, and moved on.

With Kale Yeah! students thought about potential flaws in their data: for example, shy students in the focus groups repeating what the previous person said. In doing so, this became an opportunity for deeper reflection: How do we know what we think we know? How do we create and organize our beliefs? This, in turn creates the context for ongoing metacognitive questioning.

Students learned important lessons about data collection in the social sciences. As a consequence, in future endeavours as researchers, the students will be more aware of potential problems in data collection. As consumers of journalism and in future academic studies, they will be better prepared to look critically at data.

As with the other case studies, Kale Yeah! was guided by one particular type of experience, the social, but interconnected with the other two. When Kale Yeah! students reflected on their focus group data, they not only engaged in a macro social experience (the food culture of their school); they concurrently engaged in an academic experience (nutrition studies, conducting a focus group and analyzing data) and personally, in thinking about their own eating habits.

A large part of what happens in school is social. Micro social experience here refers to the daily interactions amongst students and between students and adults. These interactions provide opportunities for students to learn how to get along with one another and to help one another learn. Furthermore, classrooms develop unique personalities that can turn in different directions on the actions of individual students, groups of students, and/or the teacher.

The purpose of micro social reflection is to increase awareness of these dynamics. The group level (what “we” do) can have significant impact for the individual within the group (what “I” do). In many cases, the peer group can be said to have as much impact, if not more, than anything else. Micro social reflections often take the following form:

Facilitating micro social reflection can be powerful way of promoting deeper academic learning for all students. Maintaining positive classroom rapport, cultivating positive emotions in the room, engaging productively in interesting work, and listening to student voice and choice all help. Structuring more formal experiences in which students learn they are not alone in the experience helps students navigate a change in thought pattern from “we are having a problem with x” to “We can overcome that problem by …”

Proactive circles provide a way for students to arrive at this. They were designed by the International Institute of Restorative Practices to prevent social problems before they arise. Frequently used as an empathy building exercise to address social challenges in the classroom, they also provide structured opportunities for students to address academic issues related to the project. Proactive circles work especially well after exhibition or project completion, by structuring opportunities for students to debrief high stakes events in a supportive social environment.

Students set up the classroom in a circle with everyone in the same type of chair.

Students use a talking stick. Students are only allowed to share if they hold the talking stick.

Discussion norms are reviewed (e.g. no sidebar conversations, no laughter, no confrontation).

The facilitator proceeds with prepared questions meant to take the social, emotional, and academic temperature of the class, the questions are:

To close the circle, students ask questions, share final thoughts and feelings, or pass.

While the micro social experience takes place in the classroom, if greater value to the student’s social experience is to occur, then the “outside world’s” macro social experience must enter into the room. Simply working at the micro level is not enough to make a project socially viable. In the Kale Yeah! project students participated actively in the social world both at the micro level (working with their peers in project delivery) and at a macro level (cafeteria food choices and lunch-time activism). In doing so, the project’s rich social experience, at both the macro and micro levels, made the academic work more important and personally empowered students to do something important.

Reflection should not be tacked on to a project or unit as a quick afterthought. Instead, reflective practices should be used as ongoing processes that inform the next step and places significance upon what has already happened. Reflection operates best when it becomes a mindset that is reinforced throughout the project and moves beyond it as well.

Unfortunately, however, it may seem expedient to bypass or rush through reflection during the hurly burly of project deadlines and unforeseen circumstances. This is especially true towards the end of a project, when students and teachers are in a frenzied state of preparation before an exhibition event and exhausted afterward. Teachers should be mindful of this while not being discouraged. Place buffers in the calendar—before, during, and after important project work—that create time for reflection. In addition, be prepared with reflective go-to questions that can settle nerves or take advantage of serendipity. By taking time to think, the teacher can save time by making the next step the easier for it.

If reflection is not part of the project, teachers can fall into the very trap that they are trying to avoid: failing to authentically and meaningfully engage students. Through poor planning, bad luck, or misguided priorities we might avoid “teaching to the test” only to replace it with a single minded focus on “teaching to the product.” In other words, teachers can get stuck in a pattern where meeting project benchmarks and completing the final product becomes the PBL version of racing through curriculum in order to score highly on a standardized test. By stopping to reflect, teachers can remind students that making a product is a process and that learning occurs by reflecting on that process.

Conversely, as with all good things, it is possible to have too much reflection. If reflection becomes a repetitive chore for students, with nothing new or important surfacing, it will lose its power. If big reflections don’t connect to the goals of the project or if small reflections fail to take advantage of developments or unforeseen opportunities, students will not see their purpose.

All three of this article’s cases demonstrate that academic, personal, and social reflection must interact for deeper learning to occur. If any one of the three experience types is diminished then learning is diminished. When the student’s personal experience is confrontive or difficult, discomfort grows, and engagement in learning lost. When the student’s social experience is assumed or neglected, team cohesiveness is damaged and students become disengaged from the real world significance of their work. Academic experience in itself requires social significance and the student’s own personal interest.

Understanding the importance of rich and fully integrating experiences places a final expectation on the project. The right balance of small and big reflection creates flexibility, and students working in PBL environments will recognize how their academic, personal, and social experiences can either support or interfere with learning. They will, in other words, take one more step in the life long process of knowing themselves.