MIKE KWAS: What we really brought to the table was the fact that we did not quit. And one of the 10th grade teachers that joined last year when we started, I believe she said, it’s like you guys were the first wave at Normandy storming the beaches, taking all the hits, and just having to get through to the other side.

[MUSIC PLAYING]

ALEC PATTON: This is High Tech High Unboxed. I’m Alec Patton and that was Mike Kwas, ninth grade social studies teacher at Cheltenham high school. When Mike talks about storming the beaches of Normandy, he’s referring to the first year of project based learning at Cheltenham. This is episode three in our series about the mission to bring Project Based Learning or PBL to Cheltenham high school, a 135-year-old public school just outside Philadelphia.

In this episode, all the visions, plans, and ideas turn into reality with actual teachers and actual students. If you want to find out how the district laid the foundations for this program, we have links to the first two episodes in the show notes. But you can also jump in right here and this episode will make sense on its own. OK, here we go.

In its first year, the PBL team consisted of three ninth grade teachers. Johanna Cella teaching biology, Brian Smith teaching English, and Mike Kwas teaching social science. That was the team awaiting the student at the start of the year in September, 2017. They had their own hallway with classrooms next to each other, they had a four hour block of time from the start of school until lunch and they’d already planned their first project. Here’s Mike to explain it.

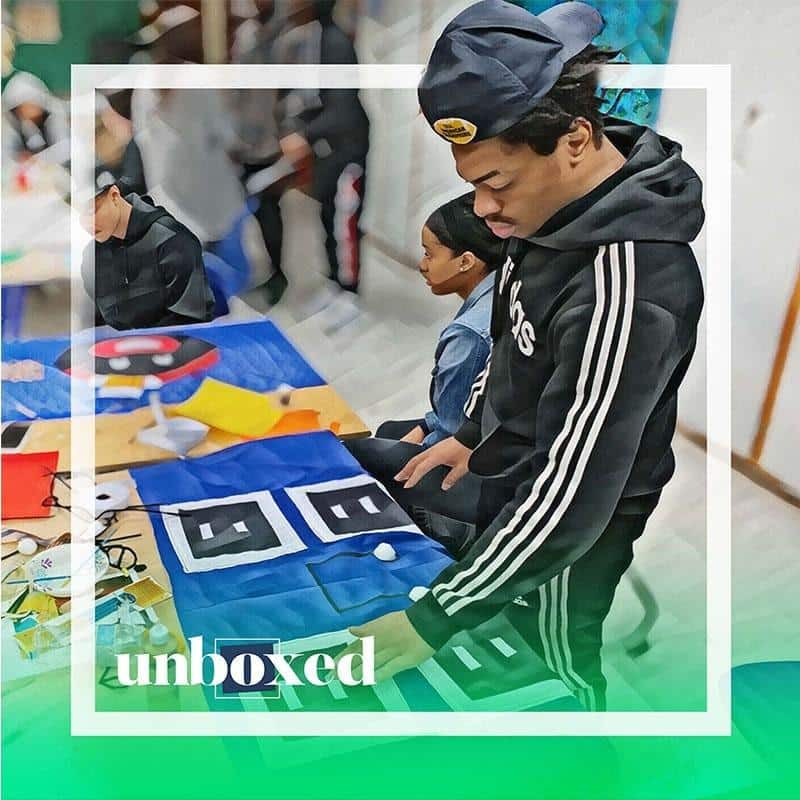

MIKE KWAS: We had worked on the time we had on a project we call it the, who am I project? Which is introspective, who the kids are and all those things. And they were going to make a big plywood construction house with their groups and they each had a panel, so to speak, expressing who they were.

ALEC PATTON: To be clear, that was the project for the start of school. All three teachers would be working on it together. They also had a radical approach to discipline.

MIKE KWAS: We wanted them to lead themselves and we thought by allowing them to create their own structure eventually, they would realize, hey, we need to police ourselves, we need some more rules, we need this, we need that. So though we were clear that there were rules, we did not want to start off by managing them like a normal classroom.

ALEC PATTON: But fundamentally, the teachers had no idea what was in store for them and they knew it. Here’s what biology teacher Johanna Cella told me when I asked her about the end of that summer just before the school year started. What were you thinking? What was going through your mind?

JOHANNA CELLA: Honestly, I think we’re just so uncertain as to what won, what we were doing exactly/what the students were going to be like that. There wasn’t too much to be quite honest. I was at the moment was in the whole come what may mindset of this is definitely going to be one of those we figure out on the fly kind of deals.

ALEC PATTON: On the first day of school, the PBL program began. Dr. Marseille, the superintendent was there for the launch along with Colin McCarthy from the Avalon foundation and the rest of the district level administrators who started the program. You can learn more about them in episodes one and two. Mike remembers the energy.

MIKE KWAS: Oh, I mean, it was exciting. The kids felt like, boy, this is a special program. We all got our props from Colin and the administration, you got these great teachers, you’re in great hands. And everybody was pretty excited. We did the newspaper tower where you build the tower out of newspapers.

While everybody else is getting taught the rules and going through your normal procedures of homework and all that, we’re making stuff and the kids are excited. We got music playing. So that was a great first day.

ALEC PATTON: Matt Pimental and Brian Reilly who are two of the architects of the program at a district level explained more about the theory behind starting with that newspaper tower game. You’ll hear Matt’s voice first in this clip and then Brian’s.

MATT PIMENTAL: The teachers really wanted to show them like day one this is not what you normally do. They did like a really simple who can build the tallest tower out of newspaper and masking tape kind of thing. Students very quickly start teaming up, they started collaborating, they started doing all the sort of things that you want to see people do in a PBL environment.

They started doing it very naturally in this competitive but silly and simple task. And then that then becomes the fodder for a discussion and conversation about what skills did you just utilize in order to accomplish this task with your peers. So I know that was a part of it and then they also had the kids going outside a lot, all like a series of games and collaborative experiences that were non-scholastic that were there to kick start a student culture that was going to be centered on kids and having kids taking a leadership role over the culture of their own group.

BRIAN RIELLY: And a lot of it was whole group. So it wasn’t we’re going to do this in the biology class and at the same time we’ll do it in English class. So it wasn’t taking the kids and separating them into three different classrooms. It was having them do that together, having the teachers do it with them. So they started the year as one collective group to set that tone that we are all PBL and we’re going to move forward together rather than in these smaller pockets which looks a lot like traditional school would have looked.

ALEC PATTON: So that was 62 students in one room. I asked one of those 62 students, Kayla about her first impressions.

KAYLA: Well, coming out of high school, freshmen, so that’s interesting. And PBL was like a whole little section for the PBL kids. And it’s just humongous room with power tools and these fancy tables and fancy chairs and four teachers in one room. And I liked it. The vibe was there. It was nice, it was calming. It was bright. I like that.

ALEC PATTON: Unlike in the rest of Cheltenham high school, there was no honors group in PBL and that was by design. Just like at High Tech High where there’s no student tracking by perceived academic ability, this was going to be a desegregated inclusive program. And just as it does it High Tech High, this approach presented distinctive challenges.

JOHANNA CELLA: We had some very intense personalities in that group. And I mean, we literally had the spectrum of personalities. I wouldn’t be surprised if this student is the valedictorian. And then we had some students who had no idea what PBL was and they just got put in there.

ALEC PATTON: And then there was the challenge of running a multi-disciplinary project.

MIKE KWAS: We got to the point like well, we have our basic foundation of what it is we want to try to do but we haven’t planned together to coordinate exactly how we’re going to do it. So we basically were staying one or two days ahead of the kids.

ALEC PATTON: And Mike, Johanna, and Brian were still figuring out how to work with each other.

MIKE KWAS: Every decision, there are a number of questions. Like OK, we’re going to do this. But there’s three personalities of how we’re going to do this. And you learn though, even though we had all this training, between the three teachers, we may have had our own impression of what we were seeing. Some of that got hashed out obviously through the planning process.

But it wasn’t until you get into real time with the kids you start to understand each other and the styles and the strengths and weaknesses of not only the kids but each of us on the team. So we were meeting. We’d go for the four hours with the kids. if I remember correctly, we did not have a lot of common prep time at that point as well.

So we would just go right from that 4-hour or 3 and 1/2 hour block to be more specific with the kids into basically debriefing the three of us sitting in the STEM lab, in the maker space. By the way, we didn’t have all our furniture quite yet. All the equipment wasn’t up and running. All the band saw, whatever it was.

So we didn’t even have stools, I think for our big works tables. So we just basically for that 40 minutes until somebody had to go teach a class and maybe even been 30 minutes. We’d either our lunch and we’d debrief and we try to figure out what we’re going to do next and then we would meet after school. At least a couple of us would meet after school trying to piece some of the things together.

ALEC PATTON: The teachers were literally making it up as they went along. But how could it have been any different? Nobody in the entire school district had ever done this before. They were making it up because that’s what you have to do when you’re doing something brand new. This was not lost on the students. Here’s Kayla again with another student, Simon.

KAYLA: It was like we were Guinea pigs really because we were the pilots. We were the Guinea pigs of PBL. And it wasn’t really the–

SIMON: It was hard to handle this freshmen because we were–

KAYLA: Changing a lot–

SIMON: immature as freshmen and then we had a lot of things put on us. We pretty much weren’t mature enough to handle all of the projects and all the freedom that we had in the space.

KAYLA: They had no idea what was going on, we had no idea what was going on. So it was just a bunch of chaos really.

ALEC PATTON: As you can imagine, there were some unrealistic expectations on both sides. From the teachers,

MIKE KWAS: We thought they were going to be, Oh. This is great. We love this. We love these projects.

ALEC PATTON: And from the students.

SIMON: A lot of us tried to almost fight the teachers. Not physically but argue how we should be being taught even though neither sides were technically correct.

ALEC PATTON: Here’s how Mike puts it.

MIKE KWAS: When you empower the kids like that, when they’re not happy, you’re going to feel it.

ALEC PATTON: Linsa Sunny a tenth grade teacher was also on the team that year but only as an observer. So she’d be ready to take the students the following year when they entered 10th grade. When she talked to Johanna, Brian, and Mike she could tell that things weren’t going entirely to plan.

LINSA SUNNY: They had lost that excitement in their eyes that we had over the summer when we were so excited to start the program.

ALEC PATTON: So what had extinguished that glint of excitement? Well, there’s the realization that they knew almost nothing about projects, there was the lack of shared planning time, and then there was that radical approach to discipline that I mentioned earlier inspired by their trip to High Tech High. For the district level team, that approach to discipline was epitomized by the teachers policy when it came to the bathroom.

MATT PIMENTAL: They were just like, well, the bathroom’s right there so just go because that was something specific they had seen from High Tech High. But it wasn’t scaffolded.

ALEC PATTON: OK. I need to clarify one thing. I taught at High Tech High for five years and in my classes, students checked with me before going to the bathroom. So this total bathroom freedom whether scaffold or otherwise, is not a core part of High Tech High’s disciplinary policy. Anyway I asked Kayla and Simon about this. And at first they rejected the premise of this policy caused any problems.

KAYLA: The bathrooms are literally right across the hall from the PBL room we were in freshman. So I don’t know about that.

ALEC PATTON: But Kayla did agree with the key point.

KAYLA: I mean, maybe the hallways. Because we were freshmen, we were immature, so if we go in the hallway of course they probably want to be loud and start playing around. I guess that was a problem.

ALEC PATTON: And remember this noise is happening in the hallway of a big mostly traditional high school. Actually, it’s worse than that. Here’s Charlene Collins, Cheltenham’s director of secondary education.

CHARLENE COLLINS: We had one team of our eighth graders in the building and because the teachers observed behaviors that they didn’t feel was becoming of an academic program, I think they didn’t lead kids to think that this would be a good opportunity for them. So that really created some issues for us for recruiting the year after.

ALEC PATTON: Just isolating the fact that too many kids were in the hallways how much of that set you back?

CHARLENE COLLINS: I think a great deal even with them in terms of the rest of the school community because what they saw was play and not work. And if you have kids being idle and looking idle, people are like, so what are they doing.

ALEC PATTON: Mike and the rest of the 9th grade team were highly conscious of this.

MIKE KWAS: I would say from the building level, there were a lot of raised eyebrows and rolled eyes from numerous teachers. Oh, this PBL isn’t going to work. We knew this wasn’t going to work. Why did they spend money, all this money and do all this stuff?

ALEC PATTON: All you teachers listening right now, picture a hallway in your school being remodeled for a brand new initiative launched with fanfare and local press attention where three teachers are spending an entire morning with a total of 62 kids to try out an approach to learning that sounded crazy to you from the start. If you heard that the kids are running wild, how inclined would you be to give the teachers the benefit of the doubt? With this in mind, I want to replay something that Mike said in the last episode because it bears revisiting.

MIKE KWAS: This decision is beyond my pay grade, but to look 10,000 feet up, if it was possible to start without all the fanfare and all the, guess what, everybody? We’re going to revolutionize education and just quietly do our thing, it’s possible that some things would have organically come into places without the resistance from the quote, unquote, “system.”

ALEC PATTON: When I was doing interviews with this episode, I wasn’t expecting a whole lot of specific insights about why things are going off the rails in that first semester. I mean, of course they were. No one had done this before and they were doing it extremely publicly. But in my interviews, people kept focusing on one particular detail which I recommend you pay attention to as well if you’re thinking about trying this in your own school.

This was happening in ninth grade. Why is that important? Well, prior to this year, Mike had been teaching fifth and sixth grade. He had no experience teaching ninth grade whatsoever. Brian had taught ninth grade in the past but his most recent experience was teaching creative writing in film studies neither of which ninth graders were allowed to take. Johanna was the only teacher who had been teaching ninth grade the year before.

Now, ninth grade is very much its own thing. I’ve never taught it but I’ve always regarded ninth grade teachers as the elite teachers of high school because apart from their official curriculum, they spend the year teaching middle schoolers how to be high school students. And Kayla and Simon picked up on the lack of experience from the teachers right away.

KAYLA: Since they had no idea how to teach freshmen nor that they had no idea how to teach PBL, we weren’t mature either, so it just didn’t flow.

ALEC PATTON: So what did the teachers do? How did they keep this from crashing and burning? Well, this is not the route I would have taken, but one of their more memorable innovations was the cohort meeting. An unstructured meeting of all 62 students during which teachers would leave the room watch from next door through a window and let the kids work out their issues.

MIKE KWAS: I think we had at least four or five of those. One of them started. There was some minor theft going on and we’re like, Oh. Great. How do you build community when we have some thievery?

So Johanna, she was missing a pudding or something. And so we’re like, what do we do about it? Well, if we just go through the normal routine, you know how that’s going to go. So we put them in a room.

We said, look, there’s been some concern over some theft. And Johanna said, my pudding was stolen. You guys got to sort through this. This is your group. How do you feel about it? What can we do about it?

It was something like that. And we put some prompts and we left the room. Kids would go out of the room crying, they can’t do it anymore and we’d have to all get take a different bunch of kids and put it all back together and then they meet in the room and they get back together. And they would come to some common understanding and appreciation.

ALEC PATTON: That’s cool.

MIKE KWAS: If I said I had within that first year out of my 20 years of teaching at that point, I had my best years and my worst years, sometimes in the same week.

ALEC PATTON: Not everyone was totally enamored of these meetings. Here’s Brian Smith, the English teacher. An hours worth of processing feelings I think we were spinning our wheels at times, but for Charlene this growing sense of community was a sign of hope.

CHARLENE COLLINS: I was sorry about how they were able to build a sense of community and how the kids look like they’re coming together and working collaboratively.

ALEC PATTON: What they were working collaboratively on as you may recall, was the who I am project where they were building the plywood houses that we talked about earlier. They finished that project and they had their first exhibition. This is what convinced Kayla’s parents that the PBL program was the right place for their daughter.

KAYLA: After they came to like the first exhibition and they saw that we were really learning a lot of stuff and everything, that’s when they really became onboard with PBL and they saw how I was changing and becoming more confident in myself and making more relationships, I guess.

ALEC PATTON: The exhibition was a high point for Mike Kwas

MIKE KWAS: Parents were happy, kids were happy. There were hugs, there were cheers, there were smiles.

ALEC PATTON: And for Brian Smith.

BRIAN SMITH: The students really amazed us and we saw the potential in what students can do when they’re doing something for community members, parents and a bigger group than just maybe taking a test or a quiz for a teacher to grade.

ALEC PATTON: So exhibition was a hit and the team entered winter break battered but still standing, which is how I entered every winter break when I was a teacher. But in the new year, they started to hear concerns from parents.

MIKE KWAS: In January, some of the parents of our most academically engaged started saying, well, what are they really learning? Is this program right for my kid? Are they being challenged? And here’s the other part of it.

You take honors students who have learned the system and learned the game well. Even though they know they’re not happy with it, when you pull that rug out from under them completely and now all of a sudden they’re not as secure as what they are learning or if they have the right answer because you’re saying, well, you need to think it through, I’ll guide you but I’m not going to give you the answer and they’re used to very specifics, jumping through hoops. Even some of our great kids with the projects at times would get angst over well, just tell me what it is.

ALEC PATTON: Meanwhile at the district level, Matt and Bryan were worried about the scale of the projects the teachers were tackling.

MATT PIMENTAL: One of the challenges was that first project that we did, at the time what we were thinking was that we bit off more than we could chew. It was a big project. The students actually built, they built houses that were 3 feet tall and 5 feet long and maybe 2 feet wide or about that size. Pretty large wooden structures. And that’s one of the reasons why exhibition kept getting pushed back, pushed back and also there was so much collaboration because it was trying to pull together 3 teachers.

So then the shift was like, we need to shrink this down a little bit, make this more manageable, and also potentially like partner up in different ways. So I know then it just started to become an experiment of different scales of projects. Because I know at that point, they’re like, we need to go small.

BRIAN RIELLY: I believe it too. Didn’t they separate at that point because this was a full collaborative project? And I think they just needed some time in their own content, focus on themselves.

ALEC PATTON: The decision to pause the collaboration was not entirely well received.

MIKE KWAS: Because of the lack of common planning time and what have you from the administration, like Matt and Brian Reilly and they said, look I think you guys have to move away for a while from the interdisciplinary model and go into your own silos and work with projects in your own subject. So we did that for a while and the end result was is that we felt like that really wasn’t necessarily the most rewarding. They weren’t the bigger projects that you could make something from.

ALEC PATTON: Mike’s putting it mildly. Here’s how Johanna felt.

JOHANNA CELLA: The lowest point was probably December to probably about February where me, Mike, and Brian were like, Oh, my gosh. How do we do this? We had gone so far into the deep end as far as this is what we think projects are, wait, I don’t think we know what projects are. Now we need to backtrack, how do we get out of this kind of thing.

And so what happened was that we siloed ourselves into three individual subjects and that created a whole high level of stress for literally everyone. And so it was about two months of just OK, I don’t know if the kids are feeling this. I think the kids hate us. I’m not entirely sure.

ALEC PATTON: And nothing the teachers tried seemed to be working.

MIKE KWAS: I remember getting to a point in January where it’s like my God, I don’t know what else we can do. We’ve tried every possible thing. We’ve tried interdisciplinary. We went back to regular classroom which had it’s benefits but also was not really PBL. It really was not what we saw at High Tech High. We tried giving them some outside time. We tried we tried every possible thing, but it’s not like all of a sudden we had super happy kids.

ALEC PATTON: But you got through to June somehow. So what did you do?

MIKE KWAS: We had a vision of what it should be going back to High Tech High. I think somehow even with the disappointment and the frustration and the Oh, my God. What do we do next? We knew it was too much to ask in one year that we figure it all out.

So we just hunkered down and made the best of it. And we kept going we just kept going. And I’m imagining that in many ways we improved and we didn’t realize it through that process. I mean, we probably wouldn’t have survived if we didn’t.

ALEC PATTON: There wasn’t any dramatic turnaround. Just a gradual process of figuring things out.

JOHANNA CELLA: So we thought that freedom was the answer, which as you know, is not necessarily the silver bullet or the answer to this learning. And so what we had to do very, very quickly was put in structures. And they weren’t even the full structures. We didn’t even get full structures I would say until mid-year.

Maybe like January, February was when we actually got the full structure as we possibly could have and where we had like, this is what the expectation is, this is what this means. And so I felt like it was a lot of floodwaters coming in and we were just putting sandbags up and up and up as fast as we could trying to keep things at bay

ALEC PATTON: Mike told me a little more about what they mean by structures.

MIKE KWAS: Your typical expectations and types of things. We call the professional habits instead of classroom habits or classroom behavior or whatever. We linked it to the real world and we put a point system in place. By the spring, we had all that together. And that definitely helped.

ALEC PATTON: So give me an example of a specific thing that you didn’t have in place that then you were like, OK, this has to be a professional habit.

MIKE KWAS: Well, cell phone for one thing. I came from fifth and sixth grade where they weren’t allowed to be out and they tend to follow the adults more. To ninth grade where they have their sense of independence and some of them have a definite issue with cell phone usage.

We thought the cell phone would be a great tool. Why prevent them from using something that already know how to use, we can use it as a learning tool. That whole bit. But again, for many students, they were addicted to their phones.

ALEC PATTON: They also made norms for the bathroom to Charlene’s relief.

CHARLENE COLLINS: They created norms within themselves about one notifying the teacher and how many people they’re going to let in a hallway. So now when I walk through the hallway, it’s not a bunch of kids in the hallway. Because I would literally walk in the hall my first year and be like almost having these panic attacks in cycles like, why are these kids in the hallway? And they’re just socializing.

ALEC PATTON: Inside the classroom, the teachers were getting better at designing and scaffolding projects.

MIKE KWAS: Structure also included more instructional structure. It wasn’t just a disciplinary piece, it was the instructional structure, more graphic organizers.

ALEC PATTON: And the only way to get good at project based learning is to do it. Johanna had a way of describing their first project designs that really resonated with me.

JOHANNA CELLA: We also ourselves didn’t have, I would say the strongest projects. And they weren’t necessarily built to withstand a lot of resistance, if that makes sense. They were designed so that in the ideal setting this is how they would run and this is how they would go. Maybe with a little bit of give is kids have some trip ups or whatever.

But they weren’t designed so that when the world imploded this project could still figure itself out. So if there’s a child who was so absolutely resistant, we didn’t necessarily have plan B, C, or D for them.

ALEC PATTON: Sure. So what have you learned about designing resilient projects since then?

JOHANNA CELLA: Definitely that the entire project should not hang on group components. We were very much under the impression that it was and should be group driven. And I know that now we have individual components and there’s an individual accountability piece.

And even if there is a group part, it doesn’t necessarily all hinge on every single person coming to the table every single day. It’ll probably suffer a little bit but it’s not like the whole project will just fall apart if one person either doesn’t come to the table that day or if they decide that they don’t want to do the project today. And we’ve also realized that infinite choice is not the answer. Choice within boundaries is a much better way of going about it.

ALEC PATTON: I strongly endorse everything Johanna said there. But there’s another thing about project based learning, a flip side to this gloominess and self-criticism. Even a deeply flawed and naively designed project can have elements of magic and times when everything comes together. I love the way that Matt Pimental puts it.

MATT PIMENTAL: There’d be certain days where students were doing project work and it just had that, I never know exactly I describe that, that positive noise, that good hum. It’s like there’s the good hum the bad hum. And there’d be those days where you walk in and there’s just the right amount of hush in the midst of the noise that you’re like, there’s a lot of productivity happening here.

ALEC PATTON: It’s the best. You chase that like a drug.

MATT PIMENTAL: Yeah. And then the funny thing is it could literally be like 10 minutes later and the volume is cranked up significantly more you’re like, all right. That’s over. And then 10 seconds later, you’ll be like it’s noisy again. You’re like, all right, we lost it.

ALEC PATTON: Johanna was experiencing these moments too.

JOHANNA CELLA: There’s days when they were really grinding through their projects, those were like the glimmers that made me realize what we’re doing is and can be even more awesome whereas I think back to that year before I joined PBL, it was like every day I’m like, Oh, my gosh. How can I do this? I don’t know how I’m going to get through this. And I really wasn’t seeing those like genuine sparks and love of teaching.

ALEC PATTON: I know from experience that those magical days when the project takes on a life of its own can get you through a whole lot of painful slogging. So I get why the teachers are still on board with this. But I didn’t really understand why Kayla and Simon, the students decided to stay in the program. So I asked. Here’s what Kayla told me.

KAYLA: I don’t know why I stayed. I guess I didn’t feel like I wanted to go back to a regular classroom and be the shadow in the background, being invisible I guess.

ALEC PATTON: That’s a pretty good reason.

[MUSIC PLAYING]

High Tech High Inbox was hosted and edited by me, Alec Patton. Our theme music is by Brother Hershel. In the next episode, you’ll hear what happened when Kayla, Simon and the rest of their cohort went to 10th grade and how 9th grade changed things after that first year. Thanks for listening.