What’s that thing?”

“That thing that looks like an octopus with ear muffs?”

“You mean the glomerulus in the nephron?

“The what in the who?”

“The part of the kidney that filters blood and looks all tangled up?”

“Yeah, that thingy…I guess.”

What students find daunting in Biology is not so much the concepts, but the amount of academic language necessary to describe these concepts. This month we began a unit on the neurosciences in my class. We will spend the next month discussing embryology, early neuronal development, the nervous system and various neurological disorders. So far this year we have covered molecular genetics, heredity, cell biology and even a little organic chemistry. Needless to say, many of these topics are dense with terminology and conceptually abstract. Nevertheless, my students are very interested in how the brain works and were eager to begin. Why do we like the things that we like? Why do we feel the way we feel? What is depression? What is anxiety? What are dreams? These types of questions involve our life experiences, and so it is not surprising that students would want to learn more about them.

To address these questions in the neurosciences, one has to begin at the beginning, which in this case is brain development. I wanted to begin with some basic information on early embryonic and fetal development and then introduce the general anatomy of the human brain. I thought this was important to cover because many genetic diseases and disorders of the brain can be detected in the first 4-8 weeks of development. In my introductory lesson about the anatomy of the brain, my students were very excited for the first twenty minutes. The room was abuzz with questions. However, by the end of the period, eyes were glazed over. Some students had entered into a cryonic torpor. Much of the lesson focused on the Latin names of structures and the vocabulary that was necessary to understand the morphology and anatomy of the brain. It constituted information overload. I realized that in order to get through this next month I was going to have to take a more playful approach.

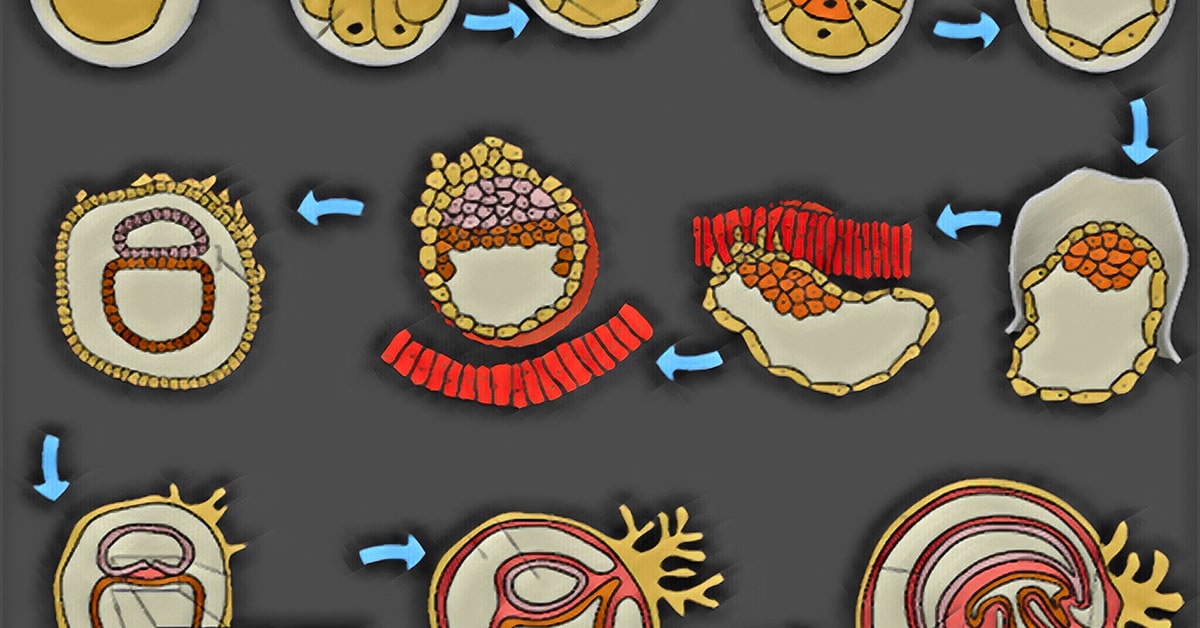

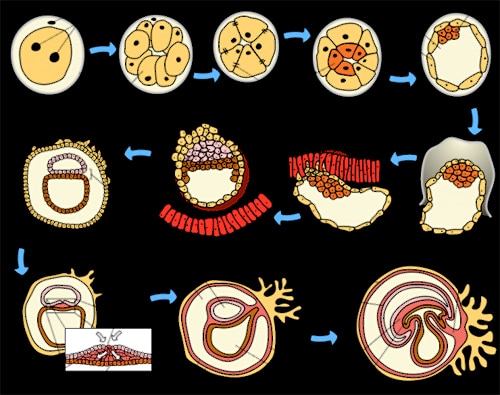

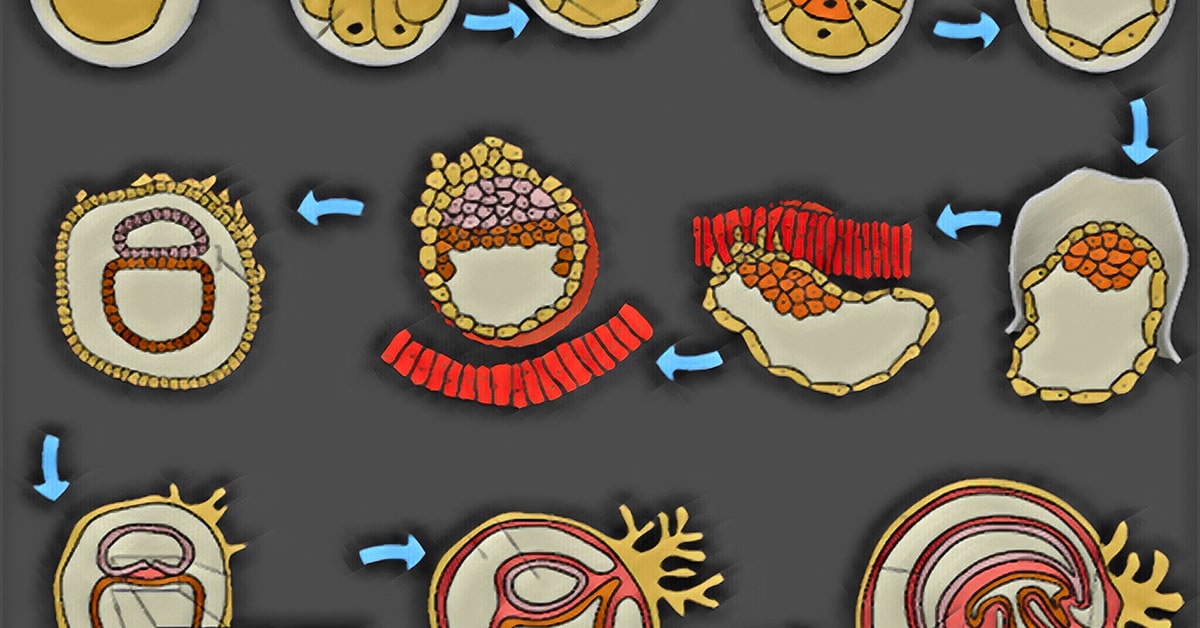

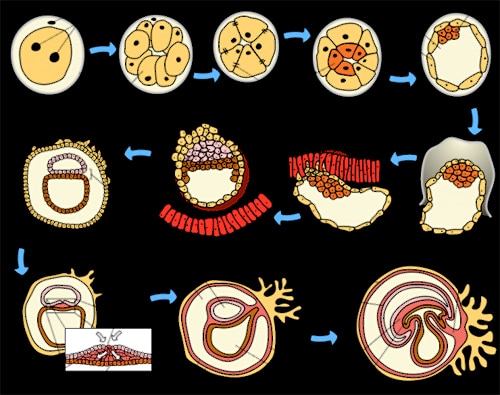

The next day in class I projected an abstract illustration (shown on the next page) on the wall of my room. I told students that we were changing gears and that we were going to do something completely different from yesterday. I asked them to take out a sheet of paper, divide it into a 4×3 grid (12 squares) and draw what they saw in each square. I drew along with them on the board. While we drew I made fun of my own abilities as an artist in the hopes that some students would feel better about their own. Some braver students poked fun at me as well.

It was interesting to see how rapidly students immersed themselves in the activity. While some students quickly scribbled down what was on the board without any attention to detail, others were more meticulous, drawing every cell and color-coding every part of what they saw in the drawing. As we drew I told students not to pay attention to the minutia but to focus on outlining the areas that were colored.

As students drew they constructed narratives about each of the individual panels.

“That one looks like a disturbed circus clown.”

“The last one looks like a mushroom.”

“I think that looks like a walnut!”

Naturally, students began to ask me what it was that we were looking at. I didn’t answer at first, so they changed their line of questioning and asked me “Why are we doing this activity?” I just smiled and turned the question around: “What do you think that we are looking at?” Some students had outlandish and fantastic theories that were fun to imagine, while others immediately guessed that these were probably the early stages of human development. I kept my poker face and refused to spill the beans.

After 20 minutes everyone was done drawing. We took the final few minutes to share out our favorite abstractions. The room was roaring with laughter from some of the stories. I then revealed the answers on the next slide. “So, congratulations! You’ve just drawn all the stages of the first three weeks of human development!” Next, the name and the day of each stage popped up on the screen, along with a description of the tissues and organs that were being formed on those days. Some students were silent. Others let out a collective “Ohhhh……Oh, I see it!!” As I walked through a description of each stage, students scribbled diligently on their papers, writing down every name and short descriptions of what was happening at each of the stages. The next day the room was full of questions about each stage.

“Why does cavitation occur?”

“What are the three primitive germ layers that we see form on the bilaminar disc?”

“Can any cell from the morula really be turned into a clone?”

Something about the activity had allowed students to understand the names associated with each stage, and the time we spent drawing allowed them to describe the processes once the context for the vocabulary was revealed. One student said, “It helped [me learn the steps], but was hard to do just because I’m not a good drawer. It was good that you put it up as long as you did, but I still needed more time with it.” Another reflected, “It was a cool activity. I think we should have guided art lessons everyday. What was cool is when you showed everything in the end because at first I was like, ‘How do I know if I’m doing this right?’ and then when you showed us everything at the end it made me want to go home and re-draw everything.”

The following weekend I had the students read and annotate an article on brain development. On Monday we broke into four groups based on students’ specific interests (early, middle, late developmental periods or a general overview). I then asked the groups to give a short presentation to the class later in the week. The presentations were rich with detail and well organized. I think that the drawing exercise that we did the previous week helped to give them the working knowledge necessary to tackle the content and provide the detailed descriptions I was looking for in the presentations.

I am discovering that teaching is about adapting the way you deliver instruction and mixing it up when things get stale. We learn best when things are novel, not recycled. Our essential questions come alive when we have new ways of exploring them, which requires that a teacher spend time creating structures in the form of games that substitute for rubrics. In a game we have a chance to win, there are rules, and there is an end point, but it is fun. We do whatever it takes to win. Whether thinking about projects or even thinking about lectures, I have begun to ask myself, how can I make this more like a game?

What’s that thing?”

“That thing that looks like an octopus with ear muffs?”

“You mean the glomerulus in the nephron?

“The what in the who?”

“The part of the kidney that filters blood and looks all tangled up?”

“Yeah, that thingy…I guess.”

What students find daunting in Biology is not so much the concepts, but the amount of academic language necessary to describe these concepts. This month we began a unit on the neurosciences in my class. We will spend the next month discussing embryology, early neuronal development, the nervous system and various neurological disorders. So far this year we have covered molecular genetics, heredity, cell biology and even a little organic chemistry. Needless to say, many of these topics are dense with terminology and conceptually abstract. Nevertheless, my students are very interested in how the brain works and were eager to begin. Why do we like the things that we like? Why do we feel the way we feel? What is depression? What is anxiety? What are dreams? These types of questions involve our life experiences, and so it is not surprising that students would want to learn more about them.

To address these questions in the neurosciences, one has to begin at the beginning, which in this case is brain development. I wanted to begin with some basic information on early embryonic and fetal development and then introduce the general anatomy of the human brain. I thought this was important to cover because many genetic diseases and disorders of the brain can be detected in the first 4-8 weeks of development. In my introductory lesson about the anatomy of the brain, my students were very excited for the first twenty minutes. The room was abuzz with questions. However, by the end of the period, eyes were glazed over. Some students had entered into a cryonic torpor. Much of the lesson focused on the Latin names of structures and the vocabulary that was necessary to understand the morphology and anatomy of the brain. It constituted information overload. I realized that in order to get through this next month I was going to have to take a more playful approach.

The next day in class I projected an abstract illustration (shown on the next page) on the wall of my room. I told students that we were changing gears and that we were going to do something completely different from yesterday. I asked them to take out a sheet of paper, divide it into a 4×3 grid (12 squares) and draw what they saw in each square. I drew along with them on the board. While we drew I made fun of my own abilities as an artist in the hopes that some students would feel better about their own. Some braver students poked fun at me as well.

It was interesting to see how rapidly students immersed themselves in the activity. While some students quickly scribbled down what was on the board without any attention to detail, others were more meticulous, drawing every cell and color-coding every part of what they saw in the drawing. As we drew I told students not to pay attention to the minutia but to focus on outlining the areas that were colored.

As students drew they constructed narratives about each of the individual panels.

“That one looks like a disturbed circus clown.”

“The last one looks like a mushroom.”

“I think that looks like a walnut!”

Naturally, students began to ask me what it was that we were looking at. I didn’t answer at first, so they changed their line of questioning and asked me “Why are we doing this activity?” I just smiled and turned the question around: “What do you think that we are looking at?” Some students had outlandish and fantastic theories that were fun to imagine, while others immediately guessed that these were probably the early stages of human development. I kept my poker face and refused to spill the beans.

After 20 minutes everyone was done drawing. We took the final few minutes to share out our favorite abstractions. The room was roaring with laughter from some of the stories. I then revealed the answers on the next slide. “So, congratulations! You’ve just drawn all the stages of the first three weeks of human development!” Next, the name and the day of each stage popped up on the screen, along with a description of the tissues and organs that were being formed on those days. Some students were silent. Others let out a collective “Ohhhh……Oh, I see it!!” As I walked through a description of each stage, students scribbled diligently on their papers, writing down every name and short descriptions of what was happening at each of the stages. The next day the room was full of questions about each stage.

“Why does cavitation occur?”

“What are the three primitive germ layers that we see form on the bilaminar disc?”

“Can any cell from the morula really be turned into a clone?”

Something about the activity had allowed students to understand the names associated with each stage, and the time we spent drawing allowed them to describe the processes once the context for the vocabulary was revealed. One student said, “It helped [me learn the steps], but was hard to do just because I’m not a good drawer. It was good that you put it up as long as you did, but I still needed more time with it.” Another reflected, “It was a cool activity. I think we should have guided art lessons everyday. What was cool is when you showed everything in the end because at first I was like, ‘How do I know if I’m doing this right?’ and then when you showed us everything at the end it made me want to go home and re-draw everything.”

The following weekend I had the students read and annotate an article on brain development. On Monday we broke into four groups based on students’ specific interests (early, middle, late developmental periods or a general overview). I then asked the groups to give a short presentation to the class later in the week. The presentations were rich with detail and well organized. I think that the drawing exercise that we did the previous week helped to give them the working knowledge necessary to tackle the content and provide the detailed descriptions I was looking for in the presentations.

I am discovering that teaching is about adapting the way you deliver instruction and mixing it up when things get stale. We learn best when things are novel, not recycled. Our essential questions come alive when we have new ways of exploring them, which requires that a teacher spend time creating structures in the form of games that substitute for rubrics. In a game we have a chance to win, there are rules, and there is an end point, but it is fun. We do whatever it takes to win. Whether thinking about projects or even thinking about lectures, I have begun to ask myself, how can I make this more like a game?