Very few of us are capable of responding to another’s success with the same sensitivity and wholeheartedness that we extend to another person’s failure . . . Responding to failure seems to bring out something good in us. It’s not that we want other people to suffer; it’s that we know better how to empathize with the person who is suffering than we do with the person who is succeeding.

—Richard Farson, Management of the Absurd

Upon coming to High Tech High, one of my biggest challenges was that I would ask my students to do something I hadn’t done since I was in sixth grade: make art. Fortunately, one of my teaching partners was Jeff Robin. Jeff is not just a fantastic artist and teacher—he is also the school “whip,” someone who pushes the school’s mission both through his own work and through his (sometimes) solicited opinions. Fortunately, I was in the asking frame of mind. The best advice that he gave me, which I’ve heard him repeat many times since, is that I should do whatever work I expect my students to do first. His reasoning is that by doing the work yourself, you can provide a model, see any potential pitfalls, and see how fun/educational it is to actually make the project. I haven’t always followed his advice, but when I have, I have been better off, as have my students. Below I discuss three times in the past year when I have tried my own projects. In each case, I learned about how to present the project to students. I have also been embarrassed and pleasantly surprised by how much better my students’ work was than my own.

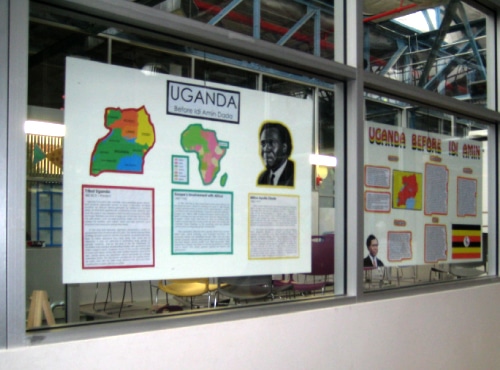

For my project on authoritarian rulers, I divided students into groups, each of which would study a different authoritarian ruler in depth. At an early phase of the project, I asked students to create two-sided foam-board displays. On one side, students would write about the country before the person’s rule, and on the other, they would discuss the ruler him or herself. For my model, I chose Saddam Hussein. I had read a lot about him over the summer in preparation for the project, and I was anxious for students to see the parallels between Iraq and their respective countries. To me, the most interesting aspect of Iraq was its borders, which brought together different ethnic groups that had historic rivalries. For my presentation, I compared three different maps of Iraq, and below each, I wrote a summary and analysis of what the borders said about Iraq and its national identity. The Photoshop process itself was informative—I hadn’t used the program since I was in middle school—and I broke out construction paper for the first time in a long time. I hung up the result in my classroom.

Our little masters of critique immediately began giving me suggestions on my own model. I had enough good sense to turn it into an activity. I even allowed Jeff to come in and critique me in front of my students. The result is that, with the assignment sheet, I included a picture of my board and the following written underneath:

“On Friday, I asked for critiques from Jeff, Kai, Gabe, and some other students, and they offered these suggestions, all of which I thought were valid:

No title!? Shame on me!

Each spot on the timeline should have a clearer label or title.

The visuals did not match the story well enough.

The pictures were too similar. Perhaps I should have moved the third (with the ethnic groups) over to replace the second (with the British borders).

The pictures should have been in color.

The colored construction paper may have been unnecessary.

The display was awfully “boxy.”

The text could have been a little bigger.

From this experience, I learned several things. First of all, I was impressed by the students’ natural critiquing skills. They clearly had practice, and they were, for the most part, kind, specific, and helpful. I also learned the importance of putting myself in the students’ shoes, not only in terms of doing the work but also in terms of subjecting myself to critique. It was a good bonding experience and a nice moment of shared empathy between me and my students. By the time the students created their own boards, they were almost universally better than mine, with very few making the mistakes that I had.

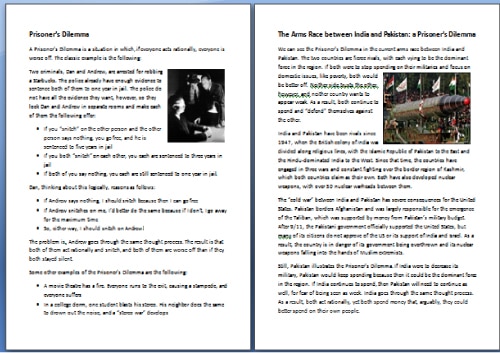

I knew from the time that I started at High Tech High that I wanted to have a project on Economics. I struggled coming up with a format, however, until two things happened. I saw Andrew Gloag’s excellent Absolute Zero book, in which students illustrated different physics concepts, and I found out that Jeff planned to make linoleum block prints with my students. With these two teacher models, I came up with a format, in which students would each create two pages of content. On one side, the student would describe an economic concept, providing a definition and examples, and on the other side, the student would write an article about a contemporary issue that could be better understood through their economic concept. For my model, I wrote about The Prisoner’s Dilemma. In contrast to my work on the historical board, I went through several revisions myself, the result being the following:

While I didn’t mind the writing aspect (I am an English teacher, after all), I skimped on doing a linoleum block myself. I knew that Jeff provided models for the students and that he would be creating that aspect of the work. What I did not account for, however, was how much my model left out the “sexiness factor” of the art. I struggled to keep students motivated because, unlike me, they could not visualize the final product. It was only when I had a student model, print and all, that the mood of the class started to change.

The lesson for me in this was that shortcuts in creating models can defeat one’s point. I had left out what I wanted to think of as “the easy part,” but my failure to create it was ultimately a cop-out, one that cost me in student engagement.

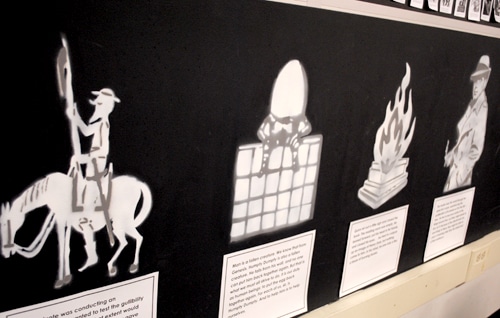

Having (in theory) learned my lesson, I spent several weeks over the summer learning how to create spray paint stencils, which I wanted my first-semester students to do based on our class book City of Glass by Paul Auster. The previous semester, my students had painted my classroom’s walls black, and I hoped to decorate without completely overhauling the room. I also wanted my students to write essays about imagery, and I needed a hook to keep them engaged. The plan, then, was for students to create a spray paint stencil of the image that they were studying-one that would accompany their essays.

For my model, I spent time re-learning Photoshop and playing with various media and image ideas. I tried using large sheets of plastic from which to cut out my images, but they were too unstable. I then tried old-school transparency film, but it wasn’t big enough. Next I tried manila folders, which were large enough but difficult to cut, especially in the middle. I finally settled on 110 lb card-stock. I realized that the card stock was easy to cut and that students could print their images directly on the card stock so that they would have an easier time cutting it out. Although this process took me a week of my summer, a destroyed shower curtain (over which I created the sprays), and a slightly pissed-off girlfriend, I had a plan.

I made mistakes choosing images as well. At first, I wanted to create a spray of Picasso’s Don Quixote, but the lines were too thin, and the image had too many “islands.” I eventually settled on an image of a pilgrim, modeled after Henry Dark, a character in the novel. Although the connection to a written image was a stretch, I had a model, which I sucessfully sprayed on card-stock.

The next step was figuring out how to spray on the walls. For my demo, I chose an image of a monkey that I thought would be fun to have on my back wall. This spray had several issues: first, I did it by myself, resulting in over-spray. I needed a better contraption to block the over and under-spray, which I eventually created with some old cardboard. I also held the spray paint too far away. Despite the instructions on the can and from sensible adults, by holding the can too far away, I made my room reek of overused spray-paint, and the white paint was dulled by the weak spray.

My final model, the one that I ultimately presented to my students, was of Humphrey Bogart (which you can see on the image to the right). Although my students didn’t see all the hard work and failures behind it, they benefited from not having to re-create my mistakes.

So, in sum, Jeff was right. In each of the above cases, my mistakes benefited my students. With the boards, I showed my flaws and built empathy; with the book, I lost student engagement for a time, making a mistake that I plan not to repeat; and with the sprays, I shielded my students from the vagaries and confusion that I struggled with at first.