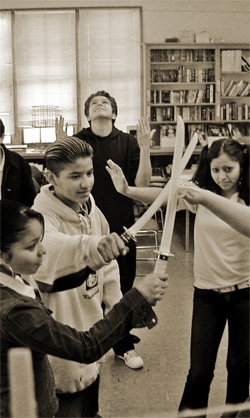

It was first period, on the first day of seventh grade. Twenty of us sat fidgeting in our seats, waiting for our English teacher. She was already five minutes late. All of a sudden, the door slammed open. A roll of toilet paper came hurtling through the air, nearly smacking me in the head. A tall woman ran into the room, tore her sandal off her foot, and banged its heel against the chalkboard. Then she stopped.

It was first period, on the first day of seventh grade. Twenty of us sat fidgeting in our seats, waiting for our English teacher. She was already five minutes late. All of a sudden, the door slammed open. A roll of toilet paper came hurtling through the air, nearly smacking me in the head. A tall woman ran into the room, tore her sandal off her foot, and banged its heel against the chalkboard. Then she stopped.

“Write,” she said. “Write down everything that you just saw.”

Later, as we took turns reading aloud what we had written, we were surprised at how differently each of our descriptions had turned out. We discovered that there are an infinite number of ways to capture the same event in writing, that the same facts can take on fresh significance when reported by a different voice. This lesson altered the way I looked at writing: it excited me about the struggle to find my own unique words to make sense of the world.

I chose a career in education because I am fascinated with learning experiences like this one, experiences that piqued my curiosity and made me eager to learn more. I am intrigued by the process whereby people come to see learning as a natural part of their lives, challenging themselves without having to be challenged by outside pressures. I am intensely curious about how to provide students with experiences that will lead them to become self-motivated lifelong learners.

Students First

The leader I want to be is, first and foremost, a fierce and tireless advocate for my students. I started my teaching career at a public high school in east Oakland, California. The students I worked with entered my classroom with a deep skepticism about school. After spending years in chaotic classrooms where teachers used up most of their energy just getting kids to quiet down, my students felt that school was largely a waste of time. With few role models in their community who had attended college and reaped its benefits, they saw little long-term value in investing effort into school.

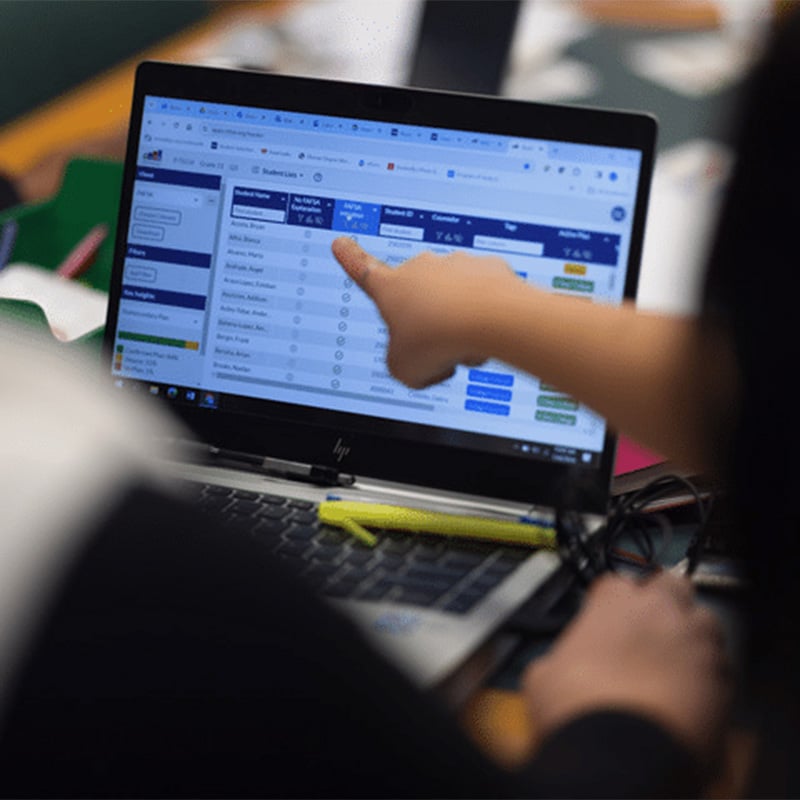

Creating learning experiences that would reignite their engagement with school became my number one priority. My colleagues and I worked together to design projects that drew on meaningful issues in our students’ lives. Our students wrote and performed a play about the effects of incarceration, created radio podcasts based on interviews with undocumented immigrants, published a guide to Oakland’s hidden restaurants, and organized an art gallery exhibiting portraits and profiles of community heroes. As much as possible, we took our students off campus to museums and theaters in San Francisco, to film festivals and spoken word competitions, to book signings and youth conferences. We brought in guest speakers—artists, activists, and scientists—to expand our students’ vision for the future. And since the mission of our school was to inspire all of our kids to go to college, not just those who were self-motivated, we raised money for college visits every year, starting in ninth grade. By the time they graduated, our students had visited many colleges and universities—public, private, and community.

These practices stemmed from a core belief that our kids deserved educational opportunities to rival that of their peers from more privileged backgrounds. In the craziness of running a school, it can be easy to lose sight of what is most important. In any school I lead, I want to always keep clearly in mind that our number one priority is to make our school a safe, inviting place that kids feel excited to spend time in each day. When things get tough, I want us to avoid blaming students and their families for their lack of academic preparedness, a common pattern I’ve seen in schools serving low-income students. Instead, I want to keep the conversation focused on what we, as teachers, can do to give our kids the best education possible. Rather than lowering expectations for what they can achieve, I want my staff to pursue relentlessly an education for our kids that equals or surpasses what they would find at wealthier, suburban schools.

Many Hats and Loving It

When I started my teaching career, I deliberately chose to teach in a charter school instead of a traditional public school because I was drawn by the promise of teacher leadership. I love the idea of teachers having a voice in the design of the curriculum and in the evolution of the school. Even as a brand new teacher, I felt a keen sense of ownership over our community because we teachers were entrusted with making decisions about every aspect of its growth, from the course offerings and discipline policies to hiring practices and budget allocations. We wore many hats and we loved it.

I want to empower teachers to take on leadership roles, to help a school evolve from the ground up. I want my colleagues to recognize that stepping up and seeking out a solution wherever they perceive a need is the main source of change at any school.

At our school in Oakland, we teachers organized ourselves into action groups around areas of school development that fired us up. After hearing former students describe the struggles they faced in their first year of college, another teacher and I decided to take a hard look at our English classes to see if we were truly preparing our students for college success. We tracked down syllabi, sample assignments, and course readers from our students’ college classes, and we connected with professors at a nearby California State University who shared their insights about the demands of college reading and writing. We also brought together a focus group of recent graduates for a rich conversation about how we could have better prepared them for their freshman year. The information we gathered from all of these sources pushed us to refine our English classes and inspired our math and science colleagues to begin a similar study of their own curriculum.

Innovation thrives when teachers have ample freedom to pursue their passions and exercise their creativity.

A Learning Community—for Teachers, too

This individual freedom needs to be balanced, though, with a sense of shared purpose and community. In cities like Oakland, too many teachers burn out and quit teaching because they take too much on their individual shoulders. The belief that it requires lone martyrs like Stand and Deliver’s Jaime Escalante—gall-bladder failure and all—to make an impact on urban education underestimates the crucial role that a school’s environment plays.

As a teacher, I craved connection. Though I was inundated almost every minute of the day with student contact, I rarely had the opportunity to converse with other adults. We were so busy juggling our myriad responsibilities that we rarely had time to reflect together on our practice—to observe each other in action, to ponder the latest educational research, and to explore our fierce wonderings.

As a school leader, I want to create a strong collegial environment where teachers feel continually supported and inspired. Rather than feeling isolated in their individual classrooms, I want teachers at my school to feel like they are part of an exciting intellectual community that is constantly making breakthroughs in the field of teaching. At most schools, unless teachers take professional development workshops in their free time, they generally have little access to new ideas for enriching their curriculum or shaking up their teaching methods. In contrast, I want teachers to tap into each other’s expertise by making teacher inquiry and reflection a centerpiece of our school’s culture. I want to be a strong instructional leader who gets the staff juiced about collaborating on innovative projects, looking at student work, and sharing effective teaching strategies.

I strive to build a school where teachers can sustain a long and fulfilling career. Whether spending time in classrooms appreciating the craft that went into their teaching, helping them connect with colleagues sharing similar interests, or bringing them a resource to inspire project planning, I want every day to be a day where I throw a shoe. Just as I left that first day of seventh grade with my curiosity provoked and my desire to learn engaged, I hope that my teachers leave every day with their curiosity provoked, feeling that our school inspires them, as much as it does their students, to be lifelong learners.