Too often when teachers get data, they don’t know what to do with it. At the University of Chicago’s Middle Grades Network, we use two protocols in succession (the first with staff members, the second with students) to transform data into effective action. The staff meeting protocol is called “What? So what? Now what?” and based on what we learn from that, we organize a “data circle” with students. Here’s what that looks like in detail.

It’s 9:30 on a Tuesday morning in October. At a Chicago Public School in the University of Chicago’s Middle Grades Network, a group of ten staff members gather to look at their first round of student experience data for the year. Present are two math teachers, two English teachers, one social studies teacher, a science teacher, two special education teachers, the assistant principal, and a counselor. The information is drawn from a survey that was given to every student in the school two weeks ago. The anticipation is palpable as the team waits to see how students responded in two areas they have been focusing on: teacher caring and classroom community.

The social studies teacher pulls up the schoolwide data to look at trends, and the team engages in a “What? So what? Now what?” protocol to analyze the data.

The first step in the protocol is for individuals to look at the data and report what they notice. These should be factual observations that stand out from their analysis. The team is happy to see that 80 percent of students believe that their teachers treat them with respect, but are surprised that only 40 percent of students think teachers care about their lives outside of school. They also notice that 75 percent of students find their classrooms to be welcoming places, but only 30 percent of students say that they feel comfortable sharing their thoughts and opinions.

In the “So what” step, team members discuss possible causes for these responses. Some argue that it might be developmentally appropriate for middle schoolers to be reticent about sharing their opinions. Even so, it is something the team wants to dig deeper into.

The team concludes with the “Now what” portion of the protocol, in which they agree on action steps based on what they have seen in the data.

They decide the next step is for the classroom teachers in the group to organize a data circle with their individual classes to learn more from the students. In this protocol, students and their teachers analyze classroom and schoolwide behavior, attendance, learning conditions, or other data together in order to come up with the next steps. Based on the data they looked at and observations made in their own classrooms, each teacher determines which area to focus on and when the circle will take place. Before leaving, each teacher creates a plan for their data circle, focusing on two pieces of data from the student survey. The team discusses some of the barriers to completing the data circle with fidelity. As a team, they decide that each teacher can determine which portions of the data circle are needed and which are optional. After finalizing the logistics (date, time, duration, area of focus), they plan to share their feedback at the next team meeting.

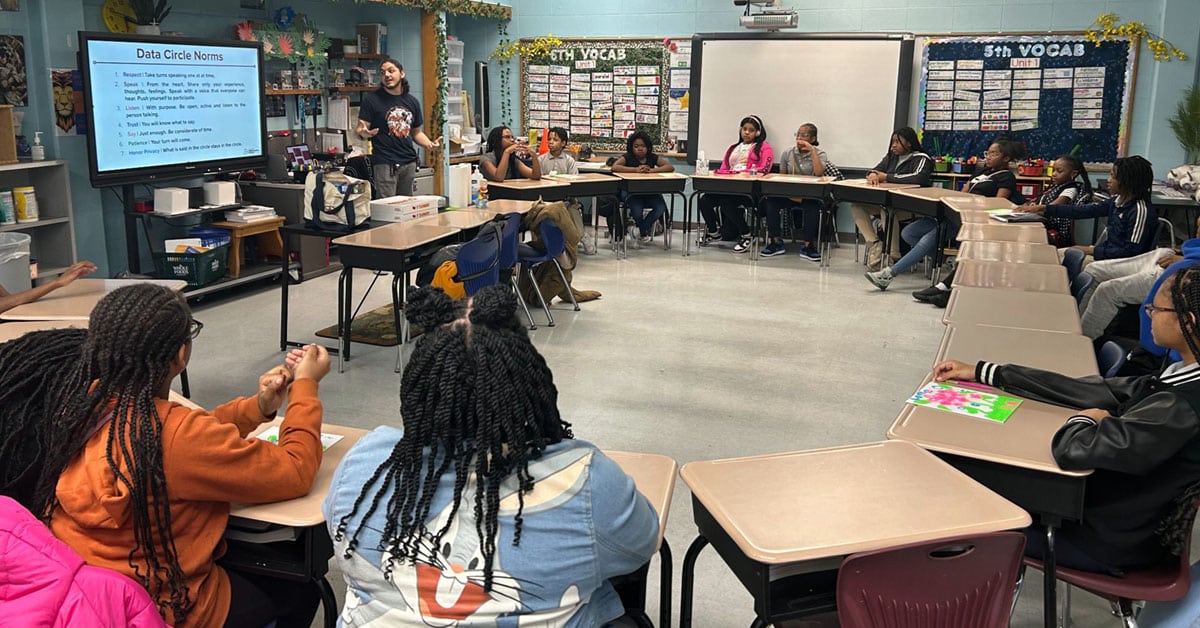

A week later, the social studies teacher facilitates her data circle. Before the class comes in, she sets up chairs in a circle. This format ensures that every person feels they are on equal footing.

Once students have come in and chosen seats, the teacher shares the agenda for the circle, setting out the following itinerary:

Sharing the agenda at the start of the circle can help ensure students are not overwhelmed, especially if this is not a common practice for the class.

Next, the teacher establishes norms for the circle. These are the same as classroom norms, but include some extra points around confidentiality and when and how to share using a talking piece, which can be any item—a stick, a whiteboard eraser, an action figure—anything that serves as a visual reminder that only the person holding the talking piece has the floor. It’s important to make sure that everyone feels safe and heard when students are sharing their personal thoughts about their teacher or class.

Once the norms and expectations are set, the circle begins with an icebreaker question. This question should be low-stakes but interesting. It could be totally unrelated to the data the students will be examining; for example, “Is a hotdog a sandwich?” It could also be connected to the data; for example, in this data circle the social studies teacher began with the question, “What is your favorite thing about school?”

Using the talking piece, students go around the circle answering the icebreaker one by once. Once every student answers the question, it’s time to dig into the first area of focus.

This teacher is particularly concerned that only 40 percent of students think their teachers care about their lives outside of school. The teacher starts the first round of the circle by sharing that data point and asking if students think it is important to feel like teachers care about their lives outside of school. Most students share that it is important, because it makes them feel like their teachers understand them and that they can share information with them. A few say that they don’t want to share details about their lives with anyone. With that in mind, the teacher turns to the discussion question. She asks what would make students feel like she cared about their lives outside of school. Some mention that they just want to be asked how they are feeling, while others want time to share about their weekends or accomplishments. Others feel like teachers don’t care because they give them so much homework that they don’t have time to do anything else over the weekend.

The teacher then starts the last round of the circle by asking what is the biggest stressor for middle school students. Students give lots of answers, including time management, prioritizing, peer pressure, and family struggles. The teacher takes in all of this information. At the end of the circle, she lets students know that she will take all the thoughts they shared and come up with a few action steps. She thanks them for their input and for sharing in such an honest way. She ensures students that she will come to them with next steps and to get additional input. She tells them that if they have any additional thoughts or questions, her door is always open.

Three weeks later, the teachers come together to share feedback from their data circles. Most had positive experiences and learned a lot about their students (among those who had a less positive experience, the biggest issues included running out of time and having difficulty persuading students to speak). The social studies teacher shared about a student who said, “Checking in with me every day is an important way to show you care about my life outside of school.” Another teacher said that his students let him know that “they are afraid of being judged when sharing their thoughts and opinions.” Additionally, teachers shared that some students said they did not feel connected to any adult in the building, while others said they wanted more opportunities to share about topics outside of content or academics.

Taking all of this feedback together, the teachers discussed possible action items and decided to implement two ideas. The first is a strategy called Relationship Mapping, in which teachers identify students who do not feel a strong connection to a staff member, and intentionally check in with them throughout the week to build stronger teacher-student relationships and make sure that every student has someone they can connect with in the building. They also decide to start asking a question of the day that students discuss at the beginning of each class to help build a stronger community around shared topics of interest.

The team is excited about these ideas, but is concerned about finding the time to implement them. They also understand that a student survey is a valuable but limited tool for collecting data, so they decide to implement informal check-ins with students to set up their next data circle.

Often when teachers get data, they don’t know what to do with it. The combination of the What? So what? Now what? protocol and the data circle is designed to help teachers go from collecting data to coming up with a course of action. After going through this process, one teacher reported that, in the words of a Middle Grades Network improvement coach, “They developed a deeper understanding of what their students need, and students started to trust their voice more. They are using the tools because they understand that care is there.”

Additionally, students shared the following as a result of being a part of the data conversation: “We all have powerful voices; my peers have a lot of thoughts and great ideas. It’s important to remember that teachers aren’t against us, they just need help to understand us.”

The teachers in the network recognize that undertaking this work takes time and does not come without challenges, but they are excited to embed these protocols in their practice. Now it’s time to figure out what data they will collect next!