In this article, we are attempting to represent the findings of a major Continuous Improvement project in a way that is thorough, rigorous, and practical.

This is new territory for us, but it’s also new territory for everyone else—there is currently no academic journal of Continuous Improvement in education anywhere in the world. If you have feedback on this article, and/or you feel inspired to write your own, we would love to hear from you—email unboxed@hightechhigh.org.

Also, if you’re pressed for time, skip to the tl;dr box at the end of the article.

Students from top quartile families are almost five times more likely to have earned a bachelor’s degree than students from bottom income quartile families (Cahalan et al., 2019). Similarly, white people are about twice as likely as African American or Latinx people to have a college degree (National Center for Education Statistics, 2019). In response to this, in 2018 the High Tech High Graduate School of Education (GSE) launched CARPE, a network of 19 high schools (and growing) in Southern California to increase the number of students who are African American, Latinx, or from low-income backgrounds who apply, enroll, and ultimately succeed in college.

To reach the goal of increased college access and based on previous work, this network began with a plan to focus on four areas: financial access, the college application process, students’ sense of belonging in college, and reducing summer melt – students who leave high school with a reported plan to attend college but do not show up in the fall. Due to the accessibility of public data on Free Application for Federal Student Aid (FAFSA) completion and with a hope of creating some early wins, the network chose to initially focus on increasing FAFSA completion rates. The network goal was to increase FAFSA completion rates from 64% to 74% by March 2, 2019 (the deadline for FAFSA in California in order to qualify for the Cal Grant, a scholarship program for lower and middle class families who meet certain grade and income requirements). By March 2nd 2019, the network improved to 70%, and by March 2nd 2020 improved further to 75%. This report focuses on our work with eight large comprehensive high schools within the CARPE network during the 2018-19 school year.

To launch this project, high school seniors from the target population were interviewed by CARPE staff via empathy interviews to learn student perspectives on college access. From these interviews, it became clear that financial aid needed to be a significant area of focus. Further, student interviews increased awareness on our team that we needed to pay more attention to working with family members, particularly on navigating FAFSA processes and related areas of financial aid. In addition to those empathy interviews, we reviewed relevant scholarly literature.[1]

The issue of FAFSA completion has received national attention recently. Every year, two million Pell grant eligible students do not file the FAFSA, which has been found to be an unnecessarily complex and poorly timed process (Gates, 2015). One of the most common reasons for failing to complete the FAFSA is the mistaken belief that the family wouldn’t qualify for financial aid (Davidson, 2013). Several studies have found that supporting families with the financial aid process leads to better student outcomes. In one study, merely giving families information about applying for financial aid did not have an impact, but accompanying this information with direct help filling out the application led to more FAFSA filing, more financial aid received, and more students enrolling in a four year college (a 7.7 percentage point increase) (Bettinger et al., 2009). In 2007-2008, 42% of community college students eligible for Pell grant funding did not fill out the FAFSA, making them unable to receive federal aid to which they were eligible (McKinney & Novak, 2013). In a study of first year community college students, not filing the FAFSA negatively impacted persistence from fall to spring semester in the first year and was the strongest predictor of persistence of all factors studied (McKinney & Novak, 2013). In one recent randomized control study, Texas families who opted into an intervention received weekly text messages from February through April about the FAFSA process and the status of their FAFSA application; this led to a six percentage point increase in FAFSA completion rates (Page & Casleman, 2019). The same authors performed a similar intervention with community college first year students which led to 14 percentage points more students persisting through spring of their second year (Castleman & Page, 2016).

Four change ideas to increase FAFSA completion: From talking with students, reviewing literature, and synthesizing findings from an earlier college access network, the CARPE team selected four practices to highlight and propose to the network (Daley, 2017).

Practice #1: Support early FAFSA completion

The CARPE team hypothesized that if students completed the FAFSA in October of senior year, they could learn in early November that they had received a Cal Grant. Knowing that tuition at a four-year college was covered, these students might be more inclined to apply to a four-year college (such as a University of California or California State University program) by the November 30 deadline.

Practice #2: Identify students who have completed FAFSA

By downloading data from the California Student Aid Commission and matching this to internal school data on all seniors, it is possible to have relatively real time data on which students have not yet completed FAFSA or have an unresolved error in their application.

Practice #3: Proactively follow up with individual students

Rather than waiting for students to come to counselors or other adults with questions, staff should reach out to students through a proactive counseling model (Dukakis et al., 2012).

Practice #4: Host Family “Sit and Do” nights

Rather than holding family nights where students receive information about the FAFSA process, research suggests that helping families fill out the FAFSA in the moment can increase FAFSA completion and college enrollment.

To support schools across the network in making improvements in FAFSA completion rates, during the 2018–19 school year, the GSE team held two two-day convenings (one in December, one in February). At these convenings, teams engaged in a number of activities, including learning about the proposed (optional) practices and brainstorming other changes. Teams also took stock of what systems were already in place in their schools to support students in completing the FAFSA as well as reviewing data on current FAFSA completion rates and goal setting for this year. Teams implemented their ideas between convenings one and two, reviewed status at convening two, and then continued to implement ideas as well as implementing new ideas after convening two and before the California FAFSA deadline of March 2. To support teams, CARPE staff coached schools between convenings via video calls and on-site visits.

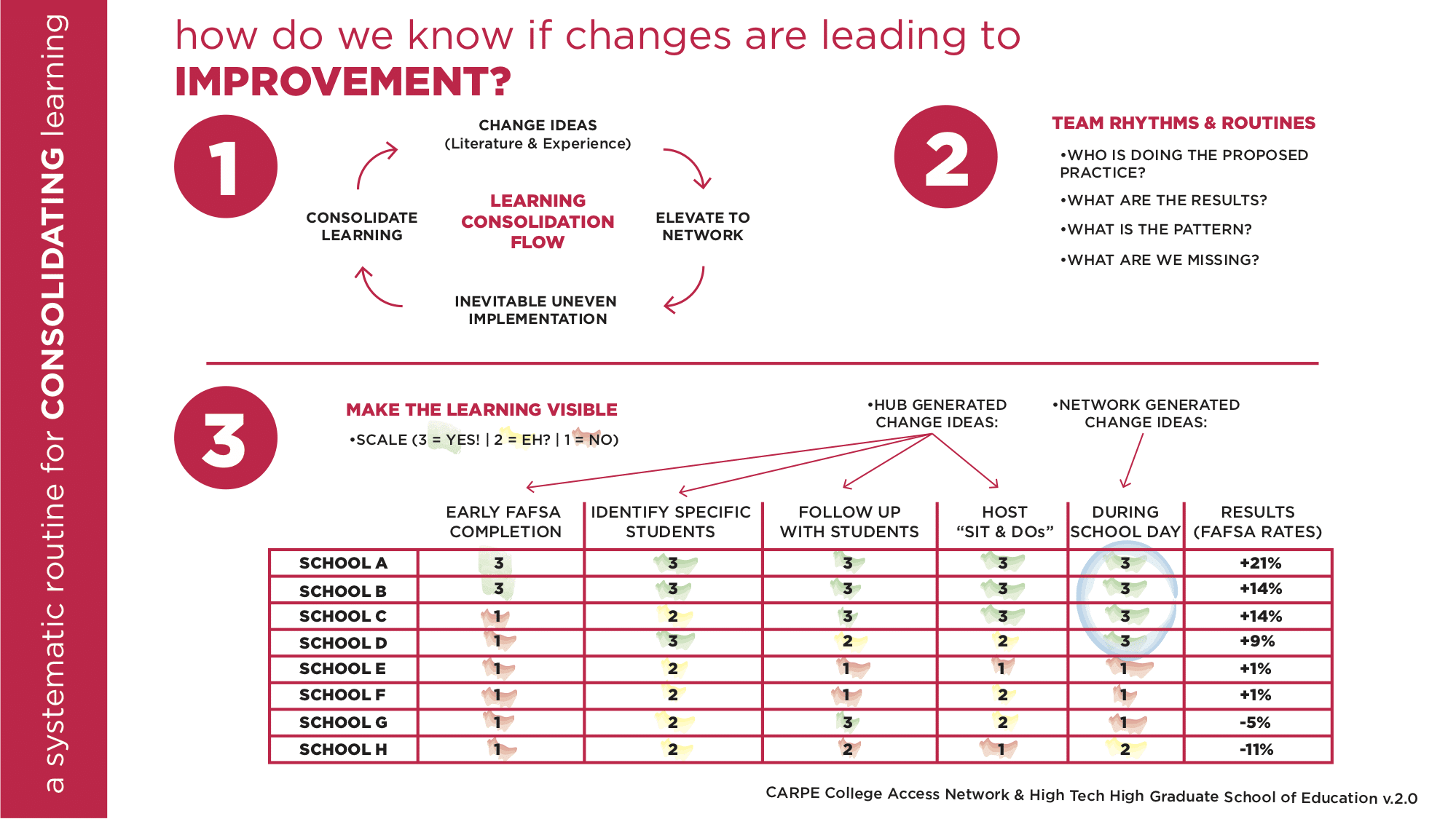

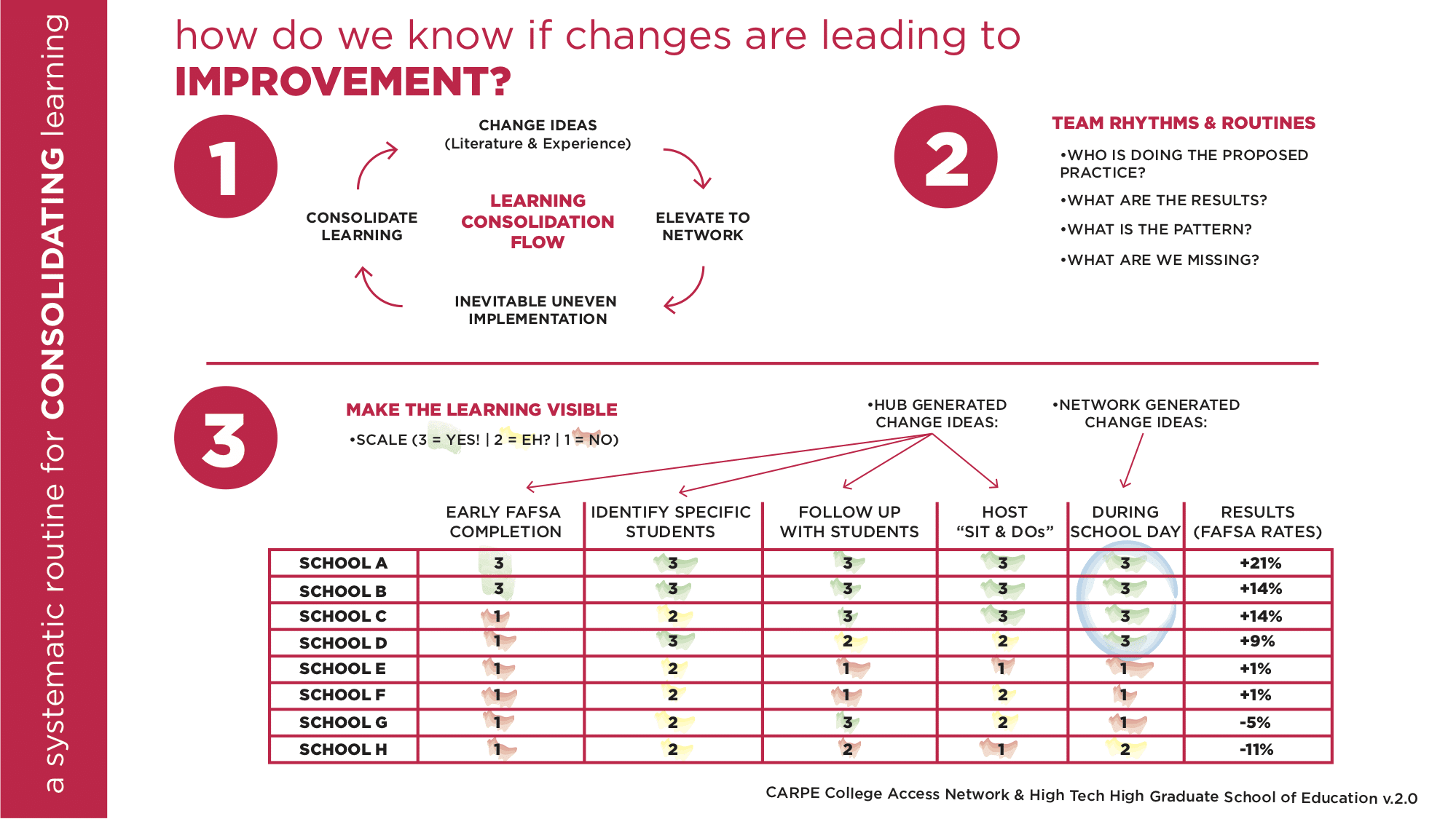

In order to investigate the extent to which the proposed practices had an impact across the network, a “consolidation of learning” activity was completed by CARPE staff [2]. The purpose of this process is to capture our learning at the end of the year, but also during the year to highlight bright spots in the network for further investigation and to surface teams that need more support. This process begins with identifying likely high leverage practices (for experience and literature), elevating these practices to a network, recognizing and acknowledging that there will be uneven implementation of these practices, and then using that unevenness as a natural experiment to investigate if doing these practices actually leads to the intended outcomes (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: A Systematic Routine for Consolidating Learning (Image created by Enrique Lugo and Rodrigo Arancibia)

For the initial round of consolidation of learning, the CARPE team grouped the eight large comprehensive high schools (high, medium, low) based on looking at their FAFSA completion rates compared to the previous year as well as subjective CARPE staff knowledge about team functioning. Then, each school was rated by CARPE coaches on a scale of one to three on the extent to which the school implemented the proposed change ideas[3]

By completing this activity, CARPE staff gained increased confidence in the effectiveness of practices 2, 3, and 4. Practice 1 was difficult to test in year one because the first network convening was too late to propose this practice during the 2018-19 cycle.[4]

After reviewing the level of implementation of the proposed practices, CARPE staff discussed if there were other practices that schools were implementing beyond those originally proposed. By completing this analysis, an additional practice emerged: doing interventions with students and families during the school day rather than only after school. This includes taking advantage of existing opportunities at school, such as through AVID classes, advisory periods, and senior teachers who reach many or all students in class each day.

The GSE updated this chart several times throughout the spring. First, the GSE filled it out during a team meeting in January 2019 based on our own incomplete understanding. Later in the spring, network staff followed up with individual schools to understand how they had applied the suggested practices. Finally, we updated this chart with the actual results on FAFSA/Dream Act completion. Based on these official results, six of eight large comprehensive schools in the network had more students completing the document in the 2018–19 school year by the March 2 deadline. As shown in Figure 1, while the pattern is not completely clear, there is some evidence that implementing all of the five high leverage practices led to increased FAFSA completion rates. Specifically, sitting with families and doing the FAFSA/Dream Act and working with students during the school day seem particularly promising. While the evidence in this paper does not rise to the level of a randomized control trial, it has nonetheless been useful to our team to systematically check whether our ideas for how to improve are actually working.

With our increased confidence in these change ideas for increasing FAFSA, we began discussing these results with teams to encourage greater implementation in the 2019–2020 school year. Some other practices from some of the CARPE schools that seem worthy of further investigation include holding phonathons (with scripts), having childcare and dinner at family FAFSA events, exploring peer to peer supports, and identifying special supports for specific populations (e.g. Dreamers, ELL, migrant, homeless, divorced parents). Finally, while we will continue to work to increase FAFSA completion across our network, we are also shifting to other interventions aimed at summer melt, belongingness, and the college application process. We hope to share progress on this work in future reports.

1This literature review is excerpted from Daley, B. (2017). Improvement science for college, career, and civic readiness: Achieving better outcomes for traditionally underserved students through systematic, disciplined inquiry [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. University of California, San Diego.

Return to article

2Thanks to Alicia Grunow and Sandra Park from the Improvement Collective for their support in this process.

Return to article

31 = did not implement. 2 = implemented but only modestly. 3 = strong implementation of the practice.

Return to article

4 The team has since found a correlation between supporting FAFSA completion early and overall results. The highest performing CARPE schools based on overall FAFSA completion rates also have strikingly high completion rates in October (as high as 90% in small schools; as high as 50% in large comprehensive high schools).

Return to article

Bettinger, E. P., Long, B.T., Oreopoulos, P., & Sanbonmatsu, L. (2009). The role of simplification and information in college decisions: Results from the H&R Block FAFSA experiment. National Bureau of Economic Research. https://www.nber.org/papers/w15361

Cahalan, M., Perna, L. W., Yamashita, M., Wright-Kim, J., & Jiang, N. (2019). Indicators of higher education equity in the United States: 2019 historical trend report. Pell Institute for the Study of Opportunity in Higher Education. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED595444

Castleman, B. L, Page LC. (2016, Spring). Freshman year financial aid nudges: An experiment to increase FAFSA renewal and college persistence. Journal of Human Resources, 51(2), 389–415. https://doi.org/10.3368/jhr.51.2.0614-6458R

Daley, B. (2017). The $50,000 prize: An improvement project to increase Cal Grant award rates [Unpublished manuscript]. High Tech High Graduate School of Education. https://bit.ly/hthcalgrant

Daley, B. (2017). Improvement science for college, career, and civic readiness: Achieving better outcomes for traditionally underserved students through systematic, disciplined inquiry [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. University of California, San Diego.

Davidson, J. C. (2013). Increasing FAFSA completion rates: Research, policies and practices. Journal of Student Financial Aid, 43(4). https://ir.library.louisville.edu/jsfa/vol43/iss1/4/

Dukakis, K., Duong, N., de Velasco J. R., & Henderson, J. (2014, August). College access and completion among boys and young men of color: Literature review of promising practices. John W. Gardner Center for Youth and their Communities. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED573658.pdf

Gates Foundation. (2015). Better for students: Simplifying the federal financial aid process. https://postsecondary.gatesfoundation.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2015/07/FAFSA-Approach_FINAL_7_7_15.pdf

McKinney, L., & Novak, H. (2013). The relationship between FAFSA filing and persistence among first-year community college students. Community College Review 41(1), 63–85. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F0091552112469251

National Center for Education Statistics. (2019, February). Indicator 27: Educational attainment. Status and trends in the education of racial and ethnic groups. https://nces.ed.gov/programs/raceindicators/indicator_RFA.asp#info

Page, L. C., & Castleman, B. L. (2019). Customized nudging to improve FAFSA completion and income verification. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 42(1). https://doi.org/10.3102/0162373719876916

Take concrete steps to support more students in completing the FAFSA; this may increase college access and success.

Suggested practices include:

Schools and networks should follow a routine for systematically investigating whether proposed changes actually lead to improvements. Several times a year, practice a disciplined “consolidation of learning” routine including attending to which practices different schools or teachers have implemented and cross referencing this to results on important outcomes.

In this article, we are attempting to represent the findings of a major Continuous Improvement project in a way that is thorough, rigorous, and practical.

This is new territory for us, but it’s also new territory for everyone else—there is currently no academic journal of Continuous Improvement in education anywhere in the world. If you have feedback on this article, and/or you feel inspired to write your own, we would love to hear from you—email unboxed@hightechhigh.org.

Also, if you’re pressed for time, skip to the tl;dr box at the end of the article.

Students from top quartile families are almost five times more likely to have earned a bachelor’s degree than students from bottom income quartile families (Cahalan et al., 2019). Similarly, white people are about twice as likely as African American or Latinx people to have a college degree (National Center for Education Statistics, 2019). In response to this, in 2018 the High Tech High Graduate School of Education (GSE) launched CARPE, a network of 19 high schools (and growing) in Southern California to increase the number of students who are African American, Latinx, or from low-income backgrounds who apply, enroll, and ultimately succeed in college.

To reach the goal of increased college access and based on previous work, this network began with a plan to focus on four areas: financial access, the college application process, students’ sense of belonging in college, and reducing summer melt – students who leave high school with a reported plan to attend college but do not show up in the fall. Due to the accessibility of public data on Free Application for Federal Student Aid (FAFSA) completion and with a hope of creating some early wins, the network chose to initially focus on increasing FAFSA completion rates. The network goal was to increase FAFSA completion rates from 64% to 74% by March 2, 2019 (the deadline for FAFSA in California in order to qualify for the Cal Grant, a scholarship program for lower and middle class families who meet certain grade and income requirements). By March 2nd 2019, the network improved to 70%, and by March 2nd 2020 improved further to 75%. This report focuses on our work with eight large comprehensive high schools within the CARPE network during the 2018-19 school year.

To launch this project, high school seniors from the target population were interviewed by CARPE staff via empathy interviews to learn student perspectives on college access. From these interviews, it became clear that financial aid needed to be a significant area of focus. Further, student interviews increased awareness on our team that we needed to pay more attention to working with family members, particularly on navigating FAFSA processes and related areas of financial aid. In addition to those empathy interviews, we reviewed relevant scholarly literature.[1]

The issue of FAFSA completion has received national attention recently. Every year, two million Pell grant eligible students do not file the FAFSA, which has been found to be an unnecessarily complex and poorly timed process (Gates, 2015). One of the most common reasons for failing to complete the FAFSA is the mistaken belief that the family wouldn’t qualify for financial aid (Davidson, 2013). Several studies have found that supporting families with the financial aid process leads to better student outcomes. In one study, merely giving families information about applying for financial aid did not have an impact, but accompanying this information with direct help filling out the application led to more FAFSA filing, more financial aid received, and more students enrolling in a four year college (a 7.7 percentage point increase) (Bettinger et al., 2009). In 2007-2008, 42% of community college students eligible for Pell grant funding did not fill out the FAFSA, making them unable to receive federal aid to which they were eligible (McKinney & Novak, 2013). In a study of first year community college students, not filing the FAFSA negatively impacted persistence from fall to spring semester in the first year and was the strongest predictor of persistence of all factors studied (McKinney & Novak, 2013). In one recent randomized control study, Texas families who opted into an intervention received weekly text messages from February through April about the FAFSA process and the status of their FAFSA application; this led to a six percentage point increase in FAFSA completion rates (Page & Casleman, 2019). The same authors performed a similar intervention with community college first year students which led to 14 percentage points more students persisting through spring of their second year (Castleman & Page, 2016).

Four change ideas to increase FAFSA completion: From talking with students, reviewing literature, and synthesizing findings from an earlier college access network, the CARPE team selected four practices to highlight and propose to the network (Daley, 2017).

Practice #1: Support early FAFSA completion

The CARPE team hypothesized that if students completed the FAFSA in October of senior year, they could learn in early November that they had received a Cal Grant. Knowing that tuition at a four-year college was covered, these students might be more inclined to apply to a four-year college (such as a University of California or California State University program) by the November 30 deadline.

Practice #2: Identify students who have completed FAFSA

By downloading data from the California Student Aid Commission and matching this to internal school data on all seniors, it is possible to have relatively real time data on which students have not yet completed FAFSA or have an unresolved error in their application.

Practice #3: Proactively follow up with individual students

Rather than waiting for students to come to counselors or other adults with questions, staff should reach out to students through a proactive counseling model (Dukakis et al., 2012).

Practice #4: Host Family “Sit and Do” nights

Rather than holding family nights where students receive information about the FAFSA process, research suggests that helping families fill out the FAFSA in the moment can increase FAFSA completion and college enrollment.

To support schools across the network in making improvements in FAFSA completion rates, during the 2018–19 school year, the GSE team held two two-day convenings (one in December, one in February). At these convenings, teams engaged in a number of activities, including learning about the proposed (optional) practices and brainstorming other changes. Teams also took stock of what systems were already in place in their schools to support students in completing the FAFSA as well as reviewing data on current FAFSA completion rates and goal setting for this year. Teams implemented their ideas between convenings one and two, reviewed status at convening two, and then continued to implement ideas as well as implementing new ideas after convening two and before the California FAFSA deadline of March 2. To support teams, CARPE staff coached schools between convenings via video calls and on-site visits.

In order to investigate the extent to which the proposed practices had an impact across the network, a “consolidation of learning” activity was completed by CARPE staff [2]. The purpose of this process is to capture our learning at the end of the year, but also during the year to highlight bright spots in the network for further investigation and to surface teams that need more support. This process begins with identifying likely high leverage practices (for experience and literature), elevating these practices to a network, recognizing and acknowledging that there will be uneven implementation of these practices, and then using that unevenness as a natural experiment to investigate if doing these practices actually leads to the intended outcomes (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: A Systematic Routine for Consolidating Learning (Image created by Enrique Lugo and Rodrigo Arancibia)

For the initial round of consolidation of learning, the CARPE team grouped the eight large comprehensive high schools (high, medium, low) based on looking at their FAFSA completion rates compared to the previous year as well as subjective CARPE staff knowledge about team functioning. Then, each school was rated by CARPE coaches on a scale of one to three on the extent to which the school implemented the proposed change ideas[3]

By completing this activity, CARPE staff gained increased confidence in the effectiveness of practices 2, 3, and 4. Practice 1 was difficult to test in year one because the first network convening was too late to propose this practice during the 2018-19 cycle.[4]

After reviewing the level of implementation of the proposed practices, CARPE staff discussed if there were other practices that schools were implementing beyond those originally proposed. By completing this analysis, an additional practice emerged: doing interventions with students and families during the school day rather than only after school. This includes taking advantage of existing opportunities at school, such as through AVID classes, advisory periods, and senior teachers who reach many or all students in class each day.

The GSE updated this chart several times throughout the spring. First, the GSE filled it out during a team meeting in January 2019 based on our own incomplete understanding. Later in the spring, network staff followed up with individual schools to understand how they had applied the suggested practices. Finally, we updated this chart with the actual results on FAFSA/Dream Act completion. Based on these official results, six of eight large comprehensive schools in the network had more students completing the document in the 2018–19 school year by the March 2 deadline. As shown in Figure 1, while the pattern is not completely clear, there is some evidence that implementing all of the five high leverage practices led to increased FAFSA completion rates. Specifically, sitting with families and doing the FAFSA/Dream Act and working with students during the school day seem particularly promising. While the evidence in this paper does not rise to the level of a randomized control trial, it has nonetheless been useful to our team to systematically check whether our ideas for how to improve are actually working.

With our increased confidence in these change ideas for increasing FAFSA, we began discussing these results with teams to encourage greater implementation in the 2019–2020 school year. Some other practices from some of the CARPE schools that seem worthy of further investigation include holding phonathons (with scripts), having childcare and dinner at family FAFSA events, exploring peer to peer supports, and identifying special supports for specific populations (e.g. Dreamers, ELL, migrant, homeless, divorced parents). Finally, while we will continue to work to increase FAFSA completion across our network, we are also shifting to other interventions aimed at summer melt, belongingness, and the college application process. We hope to share progress on this work in future reports.

1This literature review is excerpted from Daley, B. (2017). Improvement science for college, career, and civic readiness: Achieving better outcomes for traditionally underserved students through systematic, disciplined inquiry [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. University of California, San Diego.

Return to article

2Thanks to Alicia Grunow and Sandra Park from the Improvement Collective for their support in this process.

Return to article

31 = did not implement. 2 = implemented but only modestly. 3 = strong implementation of the practice.

Return to article

4 The team has since found a correlation between supporting FAFSA completion early and overall results. The highest performing CARPE schools based on overall FAFSA completion rates also have strikingly high completion rates in October (as high as 90% in small schools; as high as 50% in large comprehensive high schools).

Return to article

Bettinger, E. P., Long, B.T., Oreopoulos, P., & Sanbonmatsu, L. (2009). The role of simplification and information in college decisions: Results from the H&R Block FAFSA experiment. National Bureau of Economic Research. https://www.nber.org/papers/w15361

Cahalan, M., Perna, L. W., Yamashita, M., Wright-Kim, J., & Jiang, N. (2019). Indicators of higher education equity in the United States: 2019 historical trend report. Pell Institute for the Study of Opportunity in Higher Education. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED595444

Castleman, B. L, Page LC. (2016, Spring). Freshman year financial aid nudges: An experiment to increase FAFSA renewal and college persistence. Journal of Human Resources, 51(2), 389–415. https://doi.org/10.3368/jhr.51.2.0614-6458R

Daley, B. (2017). The $50,000 prize: An improvement project to increase Cal Grant award rates [Unpublished manuscript]. High Tech High Graduate School of Education. https://bit.ly/hthcalgrant

Daley, B. (2017). Improvement science for college, career, and civic readiness: Achieving better outcomes for traditionally underserved students through systematic, disciplined inquiry [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. University of California, San Diego.

Davidson, J. C. (2013). Increasing FAFSA completion rates: Research, policies and practices. Journal of Student Financial Aid, 43(4). https://ir.library.louisville.edu/jsfa/vol43/iss1/4/

Dukakis, K., Duong, N., de Velasco J. R., & Henderson, J. (2014, August). College access and completion among boys and young men of color: Literature review of promising practices. John W. Gardner Center for Youth and their Communities. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED573658.pdf

Gates Foundation. (2015). Better for students: Simplifying the federal financial aid process. https://postsecondary.gatesfoundation.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2015/07/FAFSA-Approach_FINAL_7_7_15.pdf

McKinney, L., & Novak, H. (2013). The relationship between FAFSA filing and persistence among first-year community college students. Community College Review 41(1), 63–85. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F0091552112469251

National Center for Education Statistics. (2019, February). Indicator 27: Educational attainment. Status and trends in the education of racial and ethnic groups. https://nces.ed.gov/programs/raceindicators/indicator_RFA.asp#info

Page, L. C., & Castleman, B. L. (2019). Customized nudging to improve FAFSA completion and income verification. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 42(1). https://doi.org/10.3102/0162373719876916

Take concrete steps to support more students in completing the FAFSA; this may increase college access and success.

Suggested practices include:

Schools and networks should follow a routine for systematically investigating whether proposed changes actually lead to improvements. Several times a year, practice a disciplined “consolidation of learning” routine including attending to which practices different schools or teachers have implemented and cross referencing this to results on important outcomes.