In my forties, I have taken up two possibly ill-advised pursuits: skateboarding and indoor rock climbing.

Both have made my life better, and I recommend that you try them. But that’s not why I’m writing about them. I’m writing because I want you to approach school improvement like rock climbing, not skateboarding.

Indoor, top-rope climbing is optimized to facilitate improvement. When I climb, I’m attached to a rope looped over a bar at the top of the wall (hence “top rope”). My climbing partner runs the other end through an automatic braking device. We check each other before a climb to make sure everything’s secure, and as a result, I know that if I fall, I won’t drop more than a few feet before the rope catches me. This means I can try a much harder climb than I’ve ever done before, and while I could certainly injure myself (climbing walls are covered in hard objects!) I’m generally as safe climbing a more advanced route as I am climbing one I can do more easily.

Skateboarding is totally different. Falling off a skateboard hurts a lot, and if I suddenly decide that the path I’ve chosen is too hard, there is no way to stop once I’m rolling down something. So while I would be willing to try every route at my climbing gym with a top rope, I approach an even slightly more difficult skateboard obstacle with trepidation. In other words, failure on a skateboard has a decent chance of being catastrophic. But failure on a climbing wall typically just means hanging at the end of the rope while I catch my breath and ready myself to give it another try.

What does any of this have to do with improvement? Starting a school improvement project often feels like skateboarding: You won’t know what it feels like until it’s already happening, you might not be able to respond quickly enough if things don’t go as planned, and you’re doing it all above an unforgiving floor of concrete. If you feel this way about an improvement project, pause and see how you could make it more like top-rope climbing. For example, improvement expert Juliette Price recently suggested on the High Tech High Unboxed podcast that administrators limit an initial intervention to the number of students they could take out for lunch if it all goes wrong. That is to say, make it so that if you fall, you know the rope will catch you.

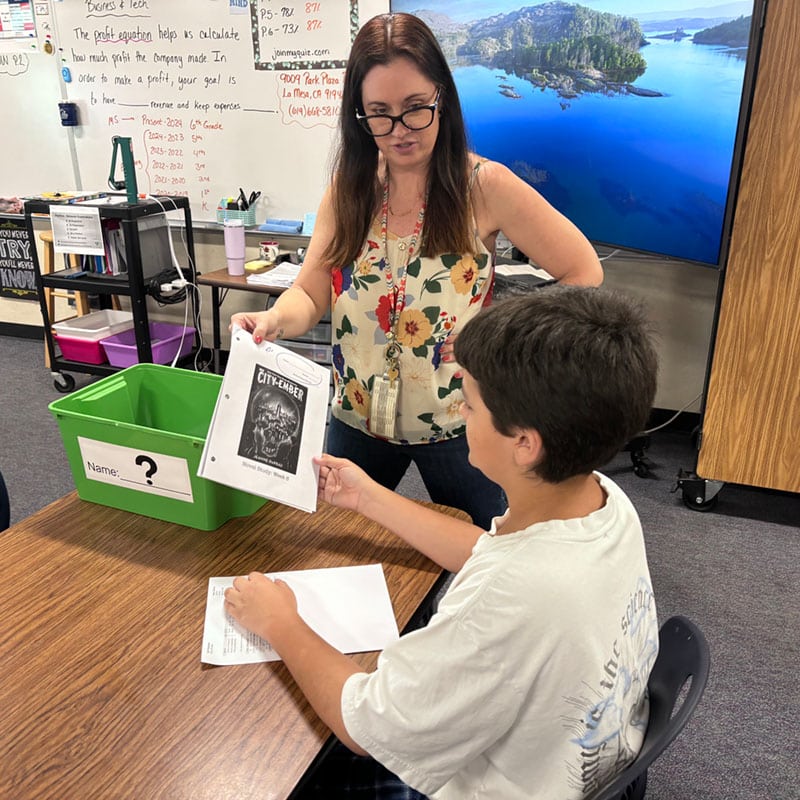

This is on my mind because this issue is full of stories of improvement and tools for improvers. You can read about how Parkway Academy in La Mesa, California created time for students to get targeted support without disrupting the school day, how in New York City, Outward Bound schools tackled disengagement in advisory, and the Teaching Matters Network for School Improvement are using identity questions to improve literacy.

You can also check out a tool for turning a school system’s existing processes into an improvement project, developed by Baltimore City Public Schools. University of Chicago’s Middle Grades Network shares a pair of protocols for looking at data first as a staff, and then with students. And RISE Network has two things for you: a strategy for measuring student absences and a version of the seven love languages designed specifically for improvement in education.

And there’s still more! Loni Berqvist explains how she determines whether or not to say yes to student ideas for changing the direction of a project, Aneesa Jamal tackles the challenge of getting students excited about reading, Peter Jana breaks down the false dichotomy between “hard” and “soft” skills, and Sara Sadek challenges us to approach educational experiences in ways that center and respect children and childhood.

Now go out and scale that wall. And try skateboarding too—just don’t use it as a model for your improvement work.

Alec Patton

Editor-in-chief