“In general, I think anyone can do what they set their mind to do as long as they know they are not alone in doing it,” Aaron Wickware said as we were wrapping up our conversation. “All they need is a little push…once they start going, they will never stop.”

It was Wickware’s first day of his second semester at California State University, Monterey Bay. A Marine Science major, and the youngest of four brothers and one sister, he is considered a “first-generation” student. Like 40% of students in the US entering post-secondary schools (Startz, 2022), he will be the first in his family to attend and graduate from a four-year college. “It was up to me and my siblings to pick up the pace,” Wickware said.

For students of color, or those who are first-generation or from low-income backgrounds—notably, Wickware intersects with all three—the path to college includes barriers and complications unknown to his White and/or wealthier peers. Knowing where to apply is its own challenge. Then, students must navigate a complicated process to apply that involves college application portals, essays, multiple deadlines, and complex financial aid forms. In California, there are additional processes to be eligible for Cal Grant, a financial-need based grant that can be a gamechanger in a student’s ability to attend higher education. Finally, students and families have to decide which college or path to choose, weighing both personal and financial factors, and do everything needed to enroll in the fall.

Many students navigate these challenges with little support. Indeed, according to the American School Counselor Association, the average ratio of students to counselors in American high schools is 408-to-1. Unsurprisingly, there remain persistent race and income gaps between who goes to college and who ultimately earns a post-secondary degree. This limitation of opportunities and income potential of young people across the country remains a civil rights crisis, perpetuating a cycle of oppression and inter-generational poverty.

Below we describe the system of support that educators at High Tech High International (HTHI), the high school Wickware attended, put in place to ensure more students like him go to colleges where they are most likely to graduate. HTHI is one of 30 high schools in Southern California involved in CARPE, a Network Improvement Community (NIC) facilitated by the Center for Research on Equity & Innovation at the High Tech High Graduate School of Education. CARPE schools—which range from small charters to large comprehensive district schools—use improvement science to ensure that students furthest from opportunity apply and enroll in colleges where they are most likely to graduate with a degree. By working together as a network, CARPE schools are able to test, refine and adapt promising practices to their own contexts, while closing equity gaps and achieving collective impact.

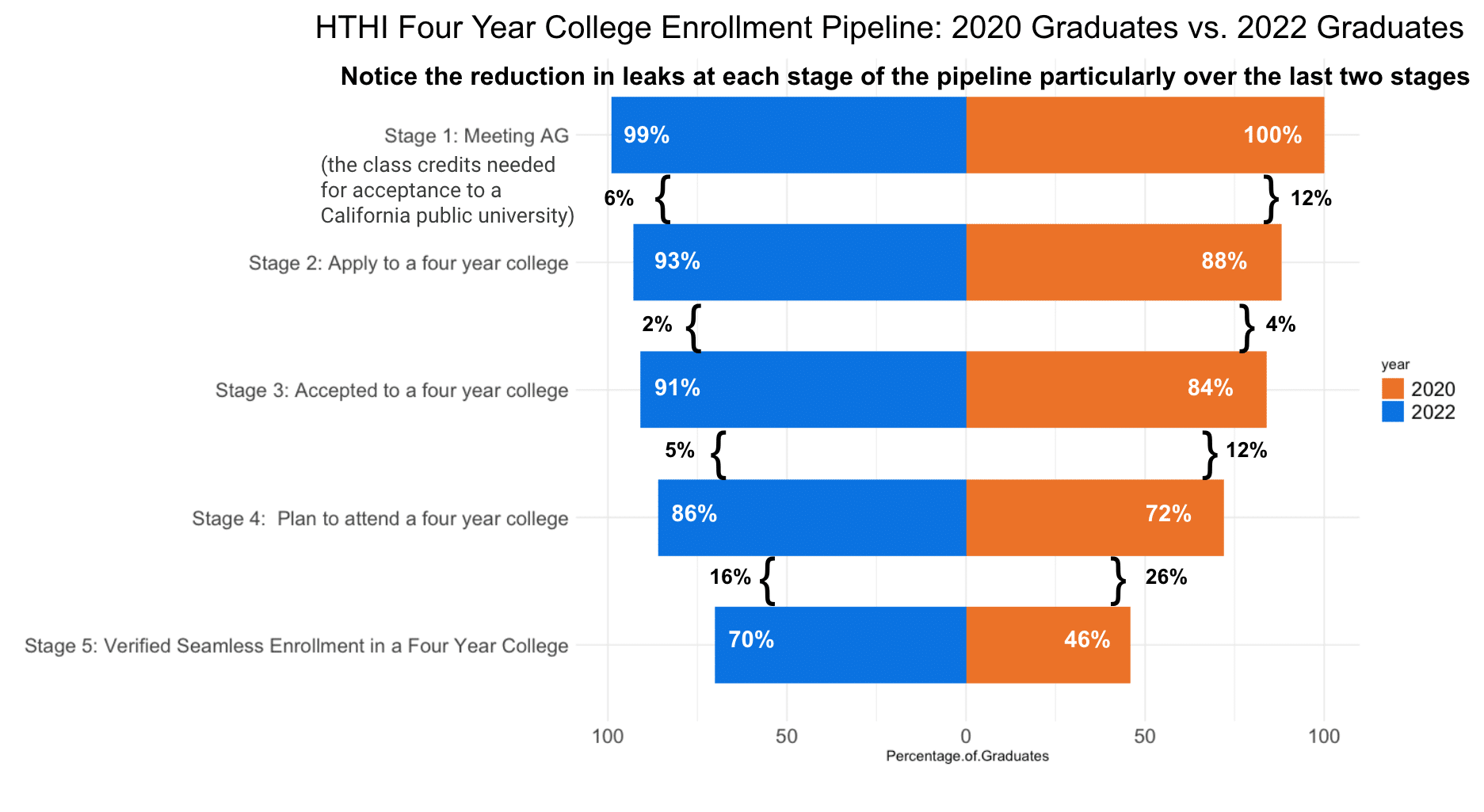

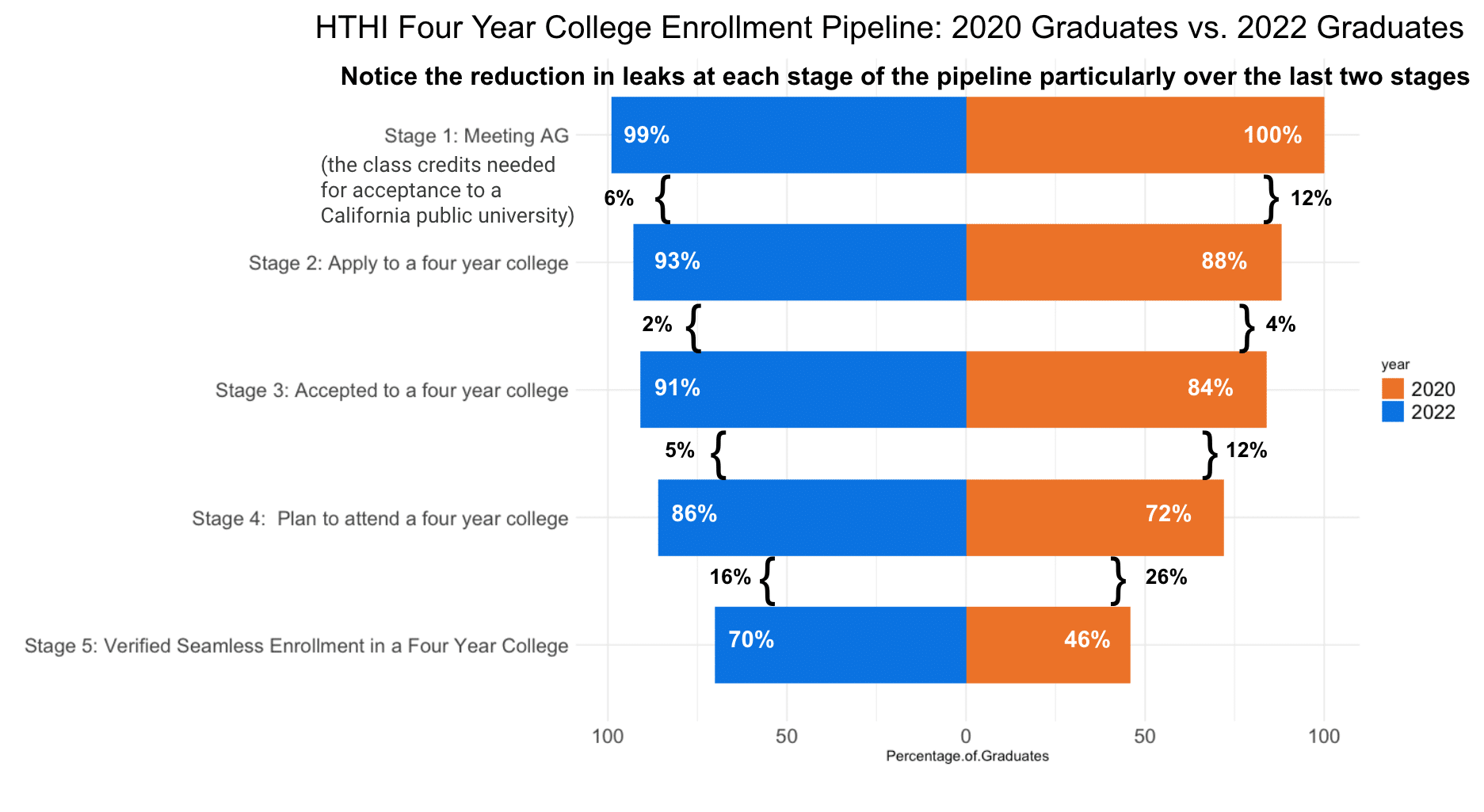

HTHI has honed many of the key practices adopted by schools across the CARPE network, and as a result, has achieved high college-going rates by reducing the number of students who fall out of the pipeline to college at each stage in the application and enrollment process (see figure 1 below). For instance, 93% of 2022 HTHI graduates reported applying to a four-year college, including 100% application completion by Latino males (which was a goal of the HTHI CARPE team). As of December 2022, National Student Clearinghouse (NSC) data showed that 70% of HTHI Seniors enrolled in a four-year college, up from 46% in 2020. This is more than double the California state average of 29% in 2020.

According to the NSC Research Center, total enrollment in four-year colleges across California decreased by two percentage points from 2020 to 2022. In contrast during the same period, four year college enrollment amongst Black, Latino or student experiencing poverty increased by more than three percentage points at CARPE Large Cohort One schools. At HTHI, four year college enrollment increased from 46 to 70 percent as shown on the funnel chart above.

CARPE schools implemented practices to cultivate a college-going culture, nurture belonging, and support critical milestones such as completing financial aid applications, identifying a list of “reach, range, and really sure” colleges to apply to with high graduation rates, completing college applications, and supporting the decision process. Several CARPE schools, like HTHI, also continued outreach in the summer months to reduce “summer melt” and ensure students enrolled in the fall.

The work at HTHI is worth noting because of how they leveraged six key practices:

Below is an outline of how these practices took form at HTHI and how they can be replicated across any school concerned with equitable college access.

Below is an outline of how these practices took form at HTHI and how they can be replicated across any school concerned with equitable college access.

HTHI joined CARPE at the inception of the network. Learning Improvement Science, they tried numerous ideas following a standard procedure: identify and try a new practice, collect data on the practice’s effectiveness, and reflect on what you learned and what you would do next—a process commonly known as a PDSA (plan, do, study, act) cycle. When asked what was the secret to their success, Erik Castillo, a HTHI college advisor of 10 years, shared how joining a network with people in the same roles, challenges and goals was pivotal to their growth. He said, “The process of using data helped us be more intentional…getting the data, figuring out what to do with it, and then taking action.”

Prior to CARPE, school counselors, teachers, and administrators might have kept track of student conversations, and where a student was in the college-going process, but this knowledge often lived with one person or wasn’t systematically updated or reviewed. CARPE’s emphasis on using a “milestone tracker” or shared spreadsheet to track each student in relation to critical college deadlines helped schools develop a routine to meet student needs. The HTHI team expressed how having shared data and clarity on each person’s role on the team was pivotal in helping assign staff members to students who might need extra support, and who may have a stronger relationship or area of needed expertise. CARPE refers to this process as “segmenting”—taking a list of students and sorting by specific markers—say race or GPA—and making a plan to meet their needs. Segmenting takes what can be an overwhelming caseload of students, and sorts it into manageable pieces for multiple people. Further, it helps teams identify and focus on equity gaps, so they are providing the most support to those who need it—for example, Black and Latino/a students who are eligible for a CalGrant.

Rather than seeing the college-going process as a counselor-specific task, HTHI builds support for college milestones into the school day and engages the whole faculty. Will Haase, a Senior math teacher on the HTHI team, shared that a major learning from the first couple years of the network was that “if [working on college applications] doesn’t happen during the school day, it doesn’t happen.” To ensure every student got the support they needed, HTHI implemented an AppFest day where seniors rotate through different classrooms and get support from the counseling staff and senior teachers to complete FAFSA and college applications.

In addition, during their advisory class period, which is similar to a “homeroom,” teachers have ongoing conversations about going to college. For example, Castillo shared that during advisory students check the status of their Cal Grant on the appropriate website, and advisory teachers add notes to the milestone tracker. The CARPE team then follows up with students in the equity group, a group of students historically furthest from opportunity, with a 3.0 GPA or higher who had issues checking their Cal Grant eligibility. This specificity allows more students to be reached by the person best suited to support them.

After these larger interventions, counselors like Castillo were able to hold more specific counseling conversations with students who were on the threshold of eligibility for certain financial aid programs, or had unclear documentation status. Haase recalled that the tiered approach to the conversation worked to meet more students’ needs, even if staff members like himself didn’t feel they had expertise. This systemic strategy of engaging the whole staff increases the frequency of confidence-building conversations with multiple adults and students about their futures.

Leveraging the advisory relationship, Haase started connecting with students over text messages before graduation to avoid “summer melt”, the phenomenon where a student is accepted into college but doesn’t enroll in the fall. According to NSC data from schools participating in the CARPE network, one in four low-income students of color from the class of 2020 indicated plans to enroll in college but didn’t go. Castleman and Page estimate that the national rate of summer melt is between 10 and 40 percent (Doglio, 2022). To successfully enroll in college full-time requires students to log-in to their college portal to access financial aid and pay tuition, register for orientation, select their courses, upload their vaccination history, register for health insurance, and identify programs on campus that provide additional academic support. This list of tasks can quickly overwhelm students, especially first-generation students like Wickware, who may start to question whether college is affordable, manageable, or where they belong.1

In an effort to stop the melt, CARPE introduced a texting campaign in which students receive a text prompting them to complete a single discrete task each week, and words of encouragement from someone who knows them well, modeled after a research-based intervention (Castleman & Page, 2014). Regular contact with students over the summer and having questions answered by a caring adult who has your back is an idea HTHI has turned into an official stipended role on the CARPE team. “There are so many components that happen out of the school culture environment,” Haase commented, “sending students a text every week to share important deadlines, encouragement, or just bug them helps them know they have an adult to help point them in the right direction.”

Research and data from the CARPE network suggest that when students feel they belong in college and enroll in college full-time during their first semester they are more likely to graduate—by a lot. In fact, historically, students who graduated from CARPE high schools in 2013 and 2014 were three times more likely to graduate from college when they enrolled full-time in their first semester of college as compared to students from CARPE high schools who enrolled part time during their first semester.2

Wickware recalled, “Will [Haase] would send me text messages like, ‘I’m really proud of you, you’ve come so far!’” Those messages meant a lot, especially as he was trying to navigate a new place where he didn’t know anyone and often felt uncertain. He added, “Knowing someone who has gone through this, and wants you to go to college and says, ‘you can do this,’ is significant.”

Focused upstream interventions impact success as well. In 2016, HTHI initiated a concentrated effort to ensure as many students as possible would be eligible for the Cal Grant program and to apply to colleges in the California State University and University of California systems. This meant focusing on the importance of GPA from the moment students begin ninth grade. HTHI started to understand what research has indicated: if a student feels a sense of belonging and is successful in their ninth grade of school, they are more than twice as likely to graduate from college with a degree (Phillips, 2019; Allen et al., 2021).

By analyzing their grade data HTHI faculty identified that a disproportionate number of students of color received lower grades than their white peers. In response, they developed ways to support students in achieving better grades with a more individualized, stronger start in their first year in high school, and recentered belonging strategies in the classroom. They hosted teacher book clubs that focused on the national problem of race-based gaps in teachers’ grading practices, and held discussions that interrogated their practices. They also started talking explicitly about Cal Grant eligibility to ninth-graders and why it should matter to them. From school leaders to classroom teachers, there was a cultural shift in what college-going meant, and it started when students entered the door as freshmen.

Haase started to notice many students, particularly first-generation students, were choosing two-year colleges over four-year schools because they assumed it was the most financially viable option. The initial sticker price of a community college can be much lower than a four-year school. However, according to NSC data from the CARPE network, students who start at a four year college are more than twice as likely to graduate from any university within six years as compared to students who start at a two year college. In addition, students who receive financial aid may end up spending less overall when going directly to a four-year college because they receive their degree more quickly and tend to move into higher paying careers. Haase commented, “Students frequently don’t accept great offers, because they are confused and parents don’t understand the reality of the offer and the payments.”

As a result, Haase took it upon himself to build a presentation using data and statistics that he taught his seniors in math class to answer the question “Is college worth it?” By providing real data and real life examples, Haase, Castillo, and other faculty helped inform students and families of the real cost of college and how financial aid can drastically reduce cost at four-year schools, and be a better investment in the long term. This meant breaking down the financial aid offered against money-earning potential, debt amounts, and predicted graduation rate (PGR) by institution—a nonobvious, tricky calculation. “This is the soft touch where details matter,” Haase said. “It makes so much sense to throw up your hands, and go to a community college unless you can help translate for students and parents…this is why so many students don’t go to a four-year school.” Another HTHI alumnus currently at California State University at San Marcos recalled this conversation with Castillo and shared, “Money is more front of mind than we often think for young people.”

Aaron Wickware remembers this conversation clearly. Wickware was considering attending Hawaiʻi Pacific University, a private school in Honolulu. He not only was accepted, but earned a significant scholarship to attend. Yet, after going through the college decision process with both Haase and Castillo, Wickware realized it wasn’t a financially viable option. With housing and other living expenses, they calculated it would cost almost $20,000 a semester of borrowed money. “It took someone to be real with you to take a step backwards and let me think it through,” he said. “At the moment, it felt like a ‘Yes!,’ but then it’s like, where is this going to leave me in ten years? That helped me step back and realize that the price at that school was just too much.” By supporting the decision process, educators can help students enroll in colleges where they are most likely to graduate, while making sound financial choices.

If there is a secret ingredient to what is happening with CARPE’s HTHI team it’s grounding people in why they do this job. They can then hold students and the mission sacred, while tending to each other with high expectations and high support. While not always explicit, centering a person’s and a team’s internal motivation for increasing more equitable student access is fundamental to the CARPE improvement community. Members of CARPE have signed on to make the work human and joyful, despite the barriers. The HTHI team created a culture of belonging where they provided tender, honest accountability for each other, and frequent high-fiving. As Castillo says about their team’s work, “It’s about relationships.”

Centering ‘the why’ of the work is likely the most radical, highest leverage improvement idea shared across the network. While oftentimes it is called “Team Excellence,” it’s the foundation for gathering, trying on new ideas, learning from mistakes, and incorporating strategies that keep students at the center. Schools that are excellent understand their motivation, then create a path and routines to see what isn’t working and for whom, and care enough to do better together.

Wickware has a new job on campus as a Second Year Experience Lead Mentor, a program founded to help low-income students of color feel a sense of belonging at CSU Monterey Bay. He likes how he can relate to students like him, and learn through the program how to help others similar to the way he felt supported. “‘I don’t know if I can do it’ is a voice that creeps up on you a lot,” he said, “Having someone who knows you and wants you to succeed…having a voice tell you ‘I believe in you,’ is just super incredible.”

1. In several studies cited by Castleman and Page (2014), the rate of summer melt was between 10 and 40% at a diverse group of three districts across the country. Perhaps most concerning was their finding that summer melt disproportionately impacts low income students: “Across these three sites, the melt rate for lower-income college intending students was two to five times as great as for their more affluent peers.”

2. NSC data provided by CARPE schools which provides data on up to eight years of graduates which allow us to report on graduates from 2013 and 2014. You need to let at least six years elapse before knowing college graduation rates.

Allen, K., Kern, M., Rozek, C., McInerney, D. & Slavich, G. (2021). Belonging: a review of conceptual issues, an integrative framework, and directions for future research. Australian Journal of Psychology, 73(2), 87-102, DOI: 10.1080/00049530.2021.1883409

American School Counselor Association. (n.d.). School Counselor Roles and Ratios. https://www.schoolcounselor.org/About-School-Counseling/School-Counselor-Roles-Ratios

Castleman, B. and Page, L. (2014). Summer melt: supporting low-income students through the transition to college. Harvard Education Press.

DataQuest. College-going rate for California high school students by postsecondary institution type, 2019-20. California Department of Education. https://dq.cde.ca.gov/dataquest/DQCensus/CGR.aspx?agglevel=State&cds=00&year=2019-20

Doglio, C. (October 26, 2022). “Tackling summer melt in the fall.” National College Attainment Network. https://www.ncan.org/news/621330/Tackling-Summer-Melt-in-the-Fall.htm

Phillips, E. (2019). The make-or-break year: solving the dropout crisis one ninth-grader at a time. The New Press.

“In general, I think anyone can do what they set their mind to do as long as they know they are not alone in doing it,” Aaron Wickware said as we were wrapping up our conversation. “All they need is a little push…once they start going, they will never stop.”

It was Wickware’s first day of his second semester at California State University, Monterey Bay. A Marine Science major, and the youngest of four brothers and one sister, he is considered a “first-generation” student. Like 40% of students in the US entering post-secondary schools (Startz, 2022), he will be the first in his family to attend and graduate from a four-year college. “It was up to me and my siblings to pick up the pace,” Wickware said.

For students of color, or those who are first-generation or from low-income backgrounds—notably, Wickware intersects with all three—the path to college includes barriers and complications unknown to his White and/or wealthier peers. Knowing where to apply is its own challenge. Then, students must navigate a complicated process to apply that involves college application portals, essays, multiple deadlines, and complex financial aid forms. In California, there are additional processes to be eligible for Cal Grant, a financial-need based grant that can be a gamechanger in a student’s ability to attend higher education. Finally, students and families have to decide which college or path to choose, weighing both personal and financial factors, and do everything needed to enroll in the fall.

Many students navigate these challenges with little support. Indeed, according to the American School Counselor Association, the average ratio of students to counselors in American high schools is 408-to-1. Unsurprisingly, there remain persistent race and income gaps between who goes to college and who ultimately earns a post-secondary degree. This limitation of opportunities and income potential of young people across the country remains a civil rights crisis, perpetuating a cycle of oppression and inter-generational poverty.

Below we describe the system of support that educators at High Tech High International (HTHI), the high school Wickware attended, put in place to ensure more students like him go to colleges where they are most likely to graduate. HTHI is one of 30 high schools in Southern California involved in CARPE, a Network Improvement Community (NIC) facilitated by the Center for Research on Equity & Innovation at the High Tech High Graduate School of Education. CARPE schools—which range from small charters to large comprehensive district schools—use improvement science to ensure that students furthest from opportunity apply and enroll in colleges where they are most likely to graduate with a degree. By working together as a network, CARPE schools are able to test, refine and adapt promising practices to their own contexts, while closing equity gaps and achieving collective impact.

HTHI has honed many of the key practices adopted by schools across the CARPE network, and as a result, has achieved high college-going rates by reducing the number of students who fall out of the pipeline to college at each stage in the application and enrollment process (see figure 1 below). For instance, 93% of 2022 HTHI graduates reported applying to a four-year college, including 100% application completion by Latino males (which was a goal of the HTHI CARPE team). As of December 2022, National Student Clearinghouse (NSC) data showed that 70% of HTHI Seniors enrolled in a four-year college, up from 46% in 2020. This is more than double the California state average of 29% in 2020.

According to the NSC Research Center, total enrollment in four-year colleges across California decreased by two percentage points from 2020 to 2022. In contrast during the same period, four year college enrollment amongst Black, Latino or student experiencing poverty increased by more than three percentage points at CARPE Large Cohort One schools. At HTHI, four year college enrollment increased from 46 to 70 percent as shown on the funnel chart above.

CARPE schools implemented practices to cultivate a college-going culture, nurture belonging, and support critical milestones such as completing financial aid applications, identifying a list of “reach, range, and really sure” colleges to apply to with high graduation rates, completing college applications, and supporting the decision process. Several CARPE schools, like HTHI, also continued outreach in the summer months to reduce “summer melt” and ensure students enrolled in the fall.

The work at HTHI is worth noting because of how they leveraged six key practices:

Below is an outline of how these practices took form at HTHI and how they can be replicated across any school concerned with equitable college access.

Below is an outline of how these practices took form at HTHI and how they can be replicated across any school concerned with equitable college access.

HTHI joined CARPE at the inception of the network. Learning Improvement Science, they tried numerous ideas following a standard procedure: identify and try a new practice, collect data on the practice’s effectiveness, and reflect on what you learned and what you would do next—a process commonly known as a PDSA (plan, do, study, act) cycle. When asked what was the secret to their success, Erik Castillo, a HTHI college advisor of 10 years, shared how joining a network with people in the same roles, challenges and goals was pivotal to their growth. He said, “The process of using data helped us be more intentional…getting the data, figuring out what to do with it, and then taking action.”

Prior to CARPE, school counselors, teachers, and administrators might have kept track of student conversations, and where a student was in the college-going process, but this knowledge often lived with one person or wasn’t systematically updated or reviewed. CARPE’s emphasis on using a “milestone tracker” or shared spreadsheet to track each student in relation to critical college deadlines helped schools develop a routine to meet student needs. The HTHI team expressed how having shared data and clarity on each person’s role on the team was pivotal in helping assign staff members to students who might need extra support, and who may have a stronger relationship or area of needed expertise. CARPE refers to this process as “segmenting”—taking a list of students and sorting by specific markers—say race or GPA—and making a plan to meet their needs. Segmenting takes what can be an overwhelming caseload of students, and sorts it into manageable pieces for multiple people. Further, it helps teams identify and focus on equity gaps, so they are providing the most support to those who need it—for example, Black and Latino/a students who are eligible for a CalGrant.

Rather than seeing the college-going process as a counselor-specific task, HTHI builds support for college milestones into the school day and engages the whole faculty. Will Haase, a Senior math teacher on the HTHI team, shared that a major learning from the first couple years of the network was that “if [working on college applications] doesn’t happen during the school day, it doesn’t happen.” To ensure every student got the support they needed, HTHI implemented an AppFest day where seniors rotate through different classrooms and get support from the counseling staff and senior teachers to complete FAFSA and college applications.

In addition, during their advisory class period, which is similar to a “homeroom,” teachers have ongoing conversations about going to college. For example, Castillo shared that during advisory students check the status of their Cal Grant on the appropriate website, and advisory teachers add notes to the milestone tracker. The CARPE team then follows up with students in the equity group, a group of students historically furthest from opportunity, with a 3.0 GPA or higher who had issues checking their Cal Grant eligibility. This specificity allows more students to be reached by the person best suited to support them.

After these larger interventions, counselors like Castillo were able to hold more specific counseling conversations with students who were on the threshold of eligibility for certain financial aid programs, or had unclear documentation status. Haase recalled that the tiered approach to the conversation worked to meet more students’ needs, even if staff members like himself didn’t feel they had expertise. This systemic strategy of engaging the whole staff increases the frequency of confidence-building conversations with multiple adults and students about their futures.

Leveraging the advisory relationship, Haase started connecting with students over text messages before graduation to avoid “summer melt”, the phenomenon where a student is accepted into college but doesn’t enroll in the fall. According to NSC data from schools participating in the CARPE network, one in four low-income students of color from the class of 2020 indicated plans to enroll in college but didn’t go. Castleman and Page estimate that the national rate of summer melt is between 10 and 40 percent (Doglio, 2022). To successfully enroll in college full-time requires students to log-in to their college portal to access financial aid and pay tuition, register for orientation, select their courses, upload their vaccination history, register for health insurance, and identify programs on campus that provide additional academic support. This list of tasks can quickly overwhelm students, especially first-generation students like Wickware, who may start to question whether college is affordable, manageable, or where they belong.1

In an effort to stop the melt, CARPE introduced a texting campaign in which students receive a text prompting them to complete a single discrete task each week, and words of encouragement from someone who knows them well, modeled after a research-based intervention (Castleman & Page, 2014). Regular contact with students over the summer and having questions answered by a caring adult who has your back is an idea HTHI has turned into an official stipended role on the CARPE team. “There are so many components that happen out of the school culture environment,” Haase commented, “sending students a text every week to share important deadlines, encouragement, or just bug them helps them know they have an adult to help point them in the right direction.”

Research and data from the CARPE network suggest that when students feel they belong in college and enroll in college full-time during their first semester they are more likely to graduate—by a lot. In fact, historically, students who graduated from CARPE high schools in 2013 and 2014 were three times more likely to graduate from college when they enrolled full-time in their first semester of college as compared to students from CARPE high schools who enrolled part time during their first semester.2

Wickware recalled, “Will [Haase] would send me text messages like, ‘I’m really proud of you, you’ve come so far!’” Those messages meant a lot, especially as he was trying to navigate a new place where he didn’t know anyone and often felt uncertain. He added, “Knowing someone who has gone through this, and wants you to go to college and says, ‘you can do this,’ is significant.”

Focused upstream interventions impact success as well. In 2016, HTHI initiated a concentrated effort to ensure as many students as possible would be eligible for the Cal Grant program and to apply to colleges in the California State University and University of California systems. This meant focusing on the importance of GPA from the moment students begin ninth grade. HTHI started to understand what research has indicated: if a student feels a sense of belonging and is successful in their ninth grade of school, they are more than twice as likely to graduate from college with a degree (Phillips, 2019; Allen et al., 2021).

By analyzing their grade data HTHI faculty identified that a disproportionate number of students of color received lower grades than their white peers. In response, they developed ways to support students in achieving better grades with a more individualized, stronger start in their first year in high school, and recentered belonging strategies in the classroom. They hosted teacher book clubs that focused on the national problem of race-based gaps in teachers’ grading practices, and held discussions that interrogated their practices. They also started talking explicitly about Cal Grant eligibility to ninth-graders and why it should matter to them. From school leaders to classroom teachers, there was a cultural shift in what college-going meant, and it started when students entered the door as freshmen.

Haase started to notice many students, particularly first-generation students, were choosing two-year colleges over four-year schools because they assumed it was the most financially viable option. The initial sticker price of a community college can be much lower than a four-year school. However, according to NSC data from the CARPE network, students who start at a four year college are more than twice as likely to graduate from any university within six years as compared to students who start at a two year college. In addition, students who receive financial aid may end up spending less overall when going directly to a four-year college because they receive their degree more quickly and tend to move into higher paying careers. Haase commented, “Students frequently don’t accept great offers, because they are confused and parents don’t understand the reality of the offer and the payments.”

As a result, Haase took it upon himself to build a presentation using data and statistics that he taught his seniors in math class to answer the question “Is college worth it?” By providing real data and real life examples, Haase, Castillo, and other faculty helped inform students and families of the real cost of college and how financial aid can drastically reduce cost at four-year schools, and be a better investment in the long term. This meant breaking down the financial aid offered against money-earning potential, debt amounts, and predicted graduation rate (PGR) by institution—a nonobvious, tricky calculation. “This is the soft touch where details matter,” Haase said. “It makes so much sense to throw up your hands, and go to a community college unless you can help translate for students and parents…this is why so many students don’t go to a four-year school.” Another HTHI alumnus currently at California State University at San Marcos recalled this conversation with Castillo and shared, “Money is more front of mind than we often think for young people.”

Aaron Wickware remembers this conversation clearly. Wickware was considering attending Hawaiʻi Pacific University, a private school in Honolulu. He not only was accepted, but earned a significant scholarship to attend. Yet, after going through the college decision process with both Haase and Castillo, Wickware realized it wasn’t a financially viable option. With housing and other living expenses, they calculated it would cost almost $20,000 a semester of borrowed money. “It took someone to be real with you to take a step backwards and let me think it through,” he said. “At the moment, it felt like a ‘Yes!,’ but then it’s like, where is this going to leave me in ten years? That helped me step back and realize that the price at that school was just too much.” By supporting the decision process, educators can help students enroll in colleges where they are most likely to graduate, while making sound financial choices.

If there is a secret ingredient to what is happening with CARPE’s HTHI team it’s grounding people in why they do this job. They can then hold students and the mission sacred, while tending to each other with high expectations and high support. While not always explicit, centering a person’s and a team’s internal motivation for increasing more equitable student access is fundamental to the CARPE improvement community. Members of CARPE have signed on to make the work human and joyful, despite the barriers. The HTHI team created a culture of belonging where they provided tender, honest accountability for each other, and frequent high-fiving. As Castillo says about their team’s work, “It’s about relationships.”

Centering ‘the why’ of the work is likely the most radical, highest leverage improvement idea shared across the network. While oftentimes it is called “Team Excellence,” it’s the foundation for gathering, trying on new ideas, learning from mistakes, and incorporating strategies that keep students at the center. Schools that are excellent understand their motivation, then create a path and routines to see what isn’t working and for whom, and care enough to do better together.

Wickware has a new job on campus as a Second Year Experience Lead Mentor, a program founded to help low-income students of color feel a sense of belonging at CSU Monterey Bay. He likes how he can relate to students like him, and learn through the program how to help others similar to the way he felt supported. “‘I don’t know if I can do it’ is a voice that creeps up on you a lot,” he said, “Having someone who knows you and wants you to succeed…having a voice tell you ‘I believe in you,’ is just super incredible.”

1. In several studies cited by Castleman and Page (2014), the rate of summer melt was between 10 and 40% at a diverse group of three districts across the country. Perhaps most concerning was their finding that summer melt disproportionately impacts low income students: “Across these three sites, the melt rate for lower-income college intending students was two to five times as great as for their more affluent peers.”

2. NSC data provided by CARPE schools which provides data on up to eight years of graduates which allow us to report on graduates from 2013 and 2014. You need to let at least six years elapse before knowing college graduation rates.

Allen, K., Kern, M., Rozek, C., McInerney, D. & Slavich, G. (2021). Belonging: a review of conceptual issues, an integrative framework, and directions for future research. Australian Journal of Psychology, 73(2), 87-102, DOI: 10.1080/00049530.2021.1883409

American School Counselor Association. (n.d.). School Counselor Roles and Ratios. https://www.schoolcounselor.org/About-School-Counseling/School-Counselor-Roles-Ratios

Castleman, B. and Page, L. (2014). Summer melt: supporting low-income students through the transition to college. Harvard Education Press.

DataQuest. College-going rate for California high school students by postsecondary institution type, 2019-20. California Department of Education. https://dq.cde.ca.gov/dataquest/DQCensus/CGR.aspx?agglevel=State&cds=00&year=2019-20

Doglio, C. (October 26, 2022). “Tackling summer melt in the fall.” National College Attainment Network. https://www.ncan.org/news/621330/Tackling-Summer-Melt-in-the-Fall.htm

Phillips, E. (2019). The make-or-break year: solving the dropout crisis one ninth-grader at a time. The New Press.