I never intended to become an advocate for teaching history in elementary school; it’s something that just sort of happened. What began as a mini-project on the California Gold Rush during my first year as a teacher has since morphed into a year-long study of American History, specifically highlighting and elevating the often untold stories of historically marginalized groups of people in our country. It has taken eight years to get this far, and there is still a long way to go, but through the process of re-learning the history I was taught, and refining how to teach that history to kids, I have come to find that this work is a crucial and joyful challenge.

The challenge is, and has always been, how to make studying the past relevant and interesting to the students I have at present. Let’s face it, the idea of studying history doesn’t exactly conjure up the most exciting memories for many of us. I can recall the mindless memorization of names, dates and places I labored through in my own education. Luckily for the generation we now teach, the theory behind learning history has shifted towards a literacy-based approach (Aguilar, 2010) where historical events are presented featuring their main characters and conflicts. Common themes can be mapped across centuries, and the stories of those who have been intentionally silenced are surfacing. I’ve attempted to bring histories to life through projects in a variety of ways over the years including hands-on building, art installations and comic books. For this particular iteration of a history project I decided to take on a storytelling medium that both intrigued and terrified me: dance.

To be very clear, at the outset of this endeavor I knew nothing about dance or choreography. Our own limitations as teachers, however, cannot limit the experiences we can offer to our students. Through a generous grant and additional funding through our Parent Association, the fourth grade team at High Tech Elementary was lucky enough to partner with Arts Education Connection San Diego (AECSD), an organization that aims to bring the arts back into classrooms through collaborative teaching. With guidance from AECSD’s arts integration specialist and dance teacher extraordinaire, Wilfred Paloma, we began to bring our vision of a history dance performance to life.

Our initial idea was to tell a story that spanned hundreds of years of American history; from colonization to the Civil War. We envisioned students creating sets and costumes that changed to show the passage of time, highlighting the “key moments” within our historical timeline. To intentionally highlight the stories of historically marginalized groups, we wanted to incorporate music and dance central to these cultures: indigenous dance and music to tell the story of colonization, traditional Chinese dance and music to tell the story of the California Gold Rush, and African dance and music to tell the history of slavery in our country. As a teaching team we talked at length about how to appropriately tell the stories of groups of people to which we did not belong, and bringing in dance teachers from these groups seemed to us to be a necessary, though not sufficient, step towards that. Unfortunately, coordinating with that many different groups of people and dance teachers, along with our 75 students, was a feat we couldn’t overcome. We talked with Wilfred and decided that we would still create multiple dance pieces depicting different narrative perspectives, but we would not appropriate music or moves that did not “belong to us.” The vision was an hour-long performance, choreographed primarily by our students. We assumed that after a few months of dance and choreography instruction our students would be able to pull together a show-stopping piece that not only demonstrated the history content they learned, but their dance and choreography skills as well.

Now, I know what you’re thinking: “Didn’t Lin-Manuel Miranda beat you to this idea years ago with a brilliant, billion dollar Broadway hit?” And the answer is yes, absolutely, and thank goodness he did. The popularity of Hamilton has sparked a huge and renewed interest in history, even among our young community of elementary students. Many of our kids knew the words to his songs and had seen the performance either live or recorded. At even the mention of a history dance performance, they were sold. Most of them.

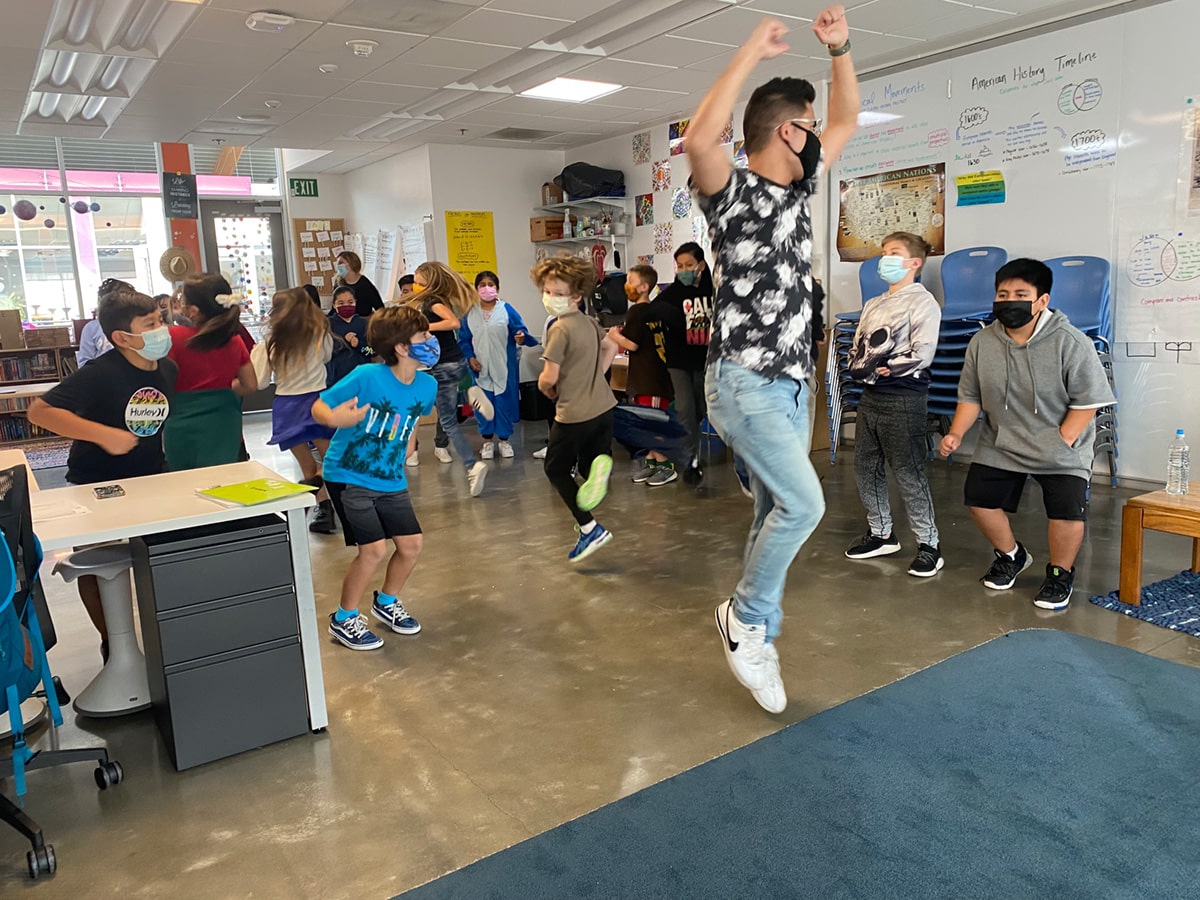

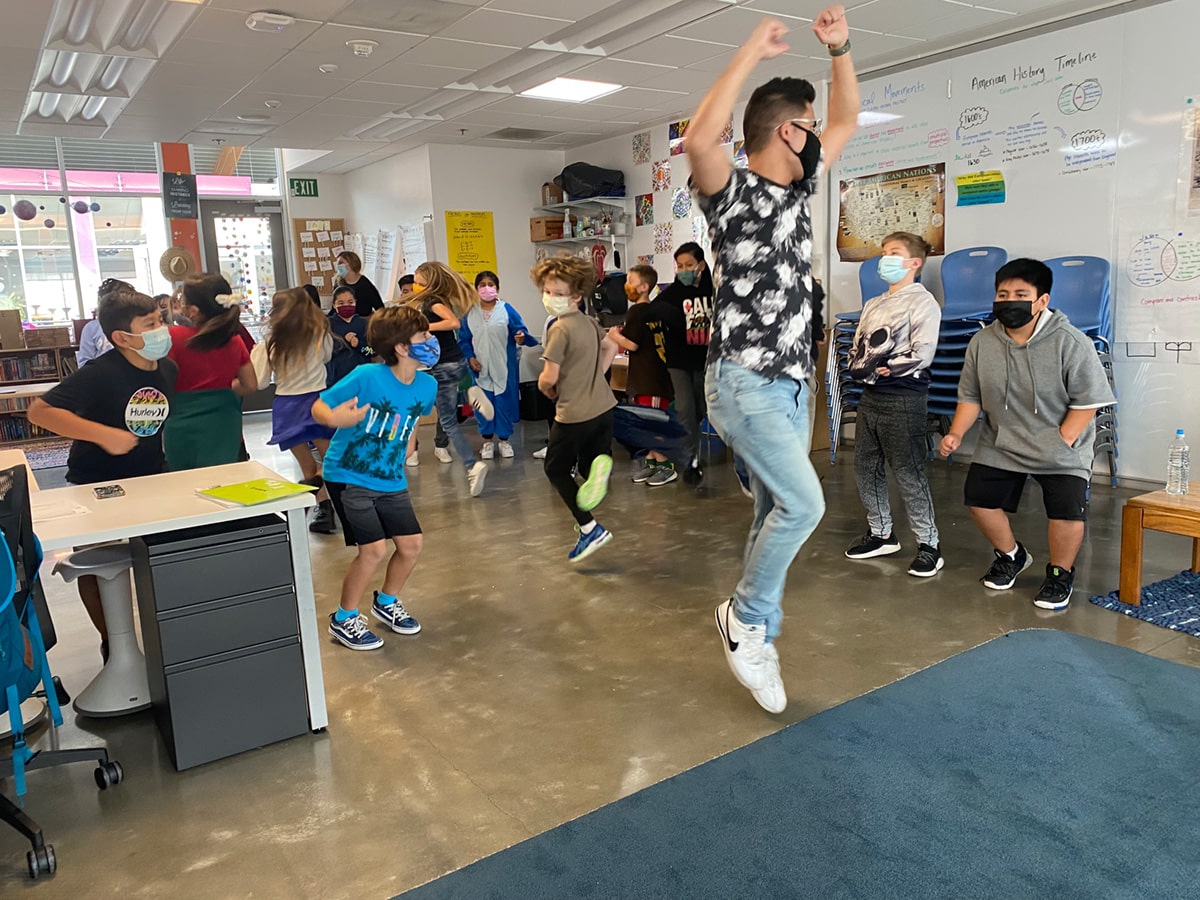

Even the most well-planned and exciting project isn’t always going to engage all learners, at least not right away. When we began this dance project, we were met, much to our surprise, with a great deal of resistance from students who were reluctant to dance, or who flat-out refused. We often had five to ten students in each of our three classes hiding under tables or in the bathroom to try to avoid our weekly dance classes. In fact, up until the moment the curtains parted on exhibition night we weren’t sure that we would have a successful performance. Resistance, though, is not a reason to stop moving forward. While it is important for students to feel connected to and contributors towards their work, it was challenging to achieve this with five to eight out of my 25 students refusing to participate on any given day. The easy thing to do would have been to assign them “alternate roles” or “other access points” and press forward with dance for those who were actually interested. We discussed what types of jobs the kids who refused to dance could do, and in the end we decided that there wasn’t going to be a back-up plan. We believed in the power of dance to tell stories; it was a cornerstone of our project design. Allowing students to miss out on that experience would prevent them from a major portion of our learning goals. While it was a constant frustration to have to beg our students to participate, to repeat the same moves over and over again, to develop self-control over their bodies, we held to the conviction that it would be worth it for the final performance we envisioned in the end.

As teachers we carefully walk the line between recognizing what the behavior of our students is trying to communicate, and how to both acknowledge their feelings and gently push their boundaries. Sometimes students are simply not ready for what we are asking them to do. Sometimes they need to stay under the table (whether literal or metaphorical) a little bit longer, and that’s okay. In our case, we knew that the nerves our shy students were feeling could be coaxed down, and we had many whole-class and individual conversations about confidence, making mistakes and supporting each other in taking risks. And you know what? We ended up getting everyone out from underneath the tables eventually.

Over the course of the project we made a few key changes to our initial idea. We simplified the performance to encompass just the history of the Civil War. Narrowing the scope shortened the total performance time to about 20 minutes which was easier for everyone to manage. We broke up the history of the Civil War into four categories and assigned a different style of dance and music to each: enslavement and the Underground Railroad, the Union and Confederate armies, the Battle of Gettysburg, and Reconstruction. We knew we wanted the Battle of Gettysburg to be a whole-grade hip hop dance battle, but we let the students choose which of the other three dance pieces they wanted to be part of. This element of choice empowered many reluctant dancers. Each group choreographed their own dance piece (with the exception of the soldiers who learned a traditional Civil War era dance called the Virginia Reel) and the students’ ideas for choreography took center stage in each piece.

Our final dance performance wasn’t perfect. We had only two rehearsals in the High Tech High Mesa theater prior to Exhibition Night and the novelty of being in the theater gave the kids a level of energy we had hoped would dissipate and didn’t. We spent all night begging them to wait quietly backstage until their turn was up. Kids missed cues, even after multiple months of practice. Moves were mixed up, costume pieces were forgotten backstage and even despite this the final performance was the best the kids had done all semester. Families walked out in awe and many shared the same sentiments: “I had no idea he could dance like that,” or, “she didn’t tell us the dance would be so good!”

If I were to do this project again there is plenty I would change—this is how I know we were onto something with this work. A project that runs smoothly from start to finish doesn’t leave room for the human element of trial and error, rarely involves risk, and often has limited learning. Even with its shortcomings, this dance project did accomplish its main goal: we were able to take a group of 75 fourth graders and turn them into dancer choreographers who were able to tell the story of the American Civil War from four different perspectives. When you watch the performance you will see the story of Black resilience and their fight for freedom via the Underground Railroad. You will watch soldiers partake in a traditional dance that helped provide respite on the battlefield and improve their tactical footwork. You will witness the Union and Confederacy battle it out for their unwavering beliefs, and you will walk through Reconstruction as our country tries to heal from the deep wounds this war caused. As you watch the video of our performance, I encourage you to consider the importance of elevating non-white voices in history, the opportunity to build empathy through taking perspective, and the relevant and lasting impact our history has on our present and future.

Aguilar, E. (2010, April 8). How to Engage Young Students in Historical Thinking. Edutopia. https://www.edutopia.org/historical-thinking-skills-K-6

I never intended to become an advocate for teaching history in elementary school; it’s something that just sort of happened. What began as a mini-project on the California Gold Rush during my first year as a teacher has since morphed into a year-long study of American History, specifically highlighting and elevating the often untold stories of historically marginalized groups of people in our country. It has taken eight years to get this far, and there is still a long way to go, but through the process of re-learning the history I was taught, and refining how to teach that history to kids, I have come to find that this work is a crucial and joyful challenge.

The challenge is, and has always been, how to make studying the past relevant and interesting to the students I have at present. Let’s face it, the idea of studying history doesn’t exactly conjure up the most exciting memories for many of us. I can recall the mindless memorization of names, dates and places I labored through in my own education. Luckily for the generation we now teach, the theory behind learning history has shifted towards a literacy-based approach (Aguilar, 2010) where historical events are presented featuring their main characters and conflicts. Common themes can be mapped across centuries, and the stories of those who have been intentionally silenced are surfacing. I’ve attempted to bring histories to life through projects in a variety of ways over the years including hands-on building, art installations and comic books. For this particular iteration of a history project I decided to take on a storytelling medium that both intrigued and terrified me: dance.

To be very clear, at the outset of this endeavor I knew nothing about dance or choreography. Our own limitations as teachers, however, cannot limit the experiences we can offer to our students. Through a generous grant and additional funding through our Parent Association, the fourth grade team at High Tech Elementary was lucky enough to partner with Arts Education Connection San Diego (AECSD), an organization that aims to bring the arts back into classrooms through collaborative teaching. With guidance from AECSD’s arts integration specialist and dance teacher extraordinaire, Wilfred Paloma, we began to bring our vision of a history dance performance to life.

Our initial idea was to tell a story that spanned hundreds of years of American history; from colonization to the Civil War. We envisioned students creating sets and costumes that changed to show the passage of time, highlighting the “key moments” within our historical timeline. To intentionally highlight the stories of historically marginalized groups, we wanted to incorporate music and dance central to these cultures: indigenous dance and music to tell the story of colonization, traditional Chinese dance and music to tell the story of the California Gold Rush, and African dance and music to tell the history of slavery in our country. As a teaching team we talked at length about how to appropriately tell the stories of groups of people to which we did not belong, and bringing in dance teachers from these groups seemed to us to be a necessary, though not sufficient, step towards that. Unfortunately, coordinating with that many different groups of people and dance teachers, along with our 75 students, was a feat we couldn’t overcome. We talked with Wilfred and decided that we would still create multiple dance pieces depicting different narrative perspectives, but we would not appropriate music or moves that did not “belong to us.” The vision was an hour-long performance, choreographed primarily by our students. We assumed that after a few months of dance and choreography instruction our students would be able to pull together a show-stopping piece that not only demonstrated the history content they learned, but their dance and choreography skills as well.

Now, I know what you’re thinking: “Didn’t Lin-Manuel Miranda beat you to this idea years ago with a brilliant, billion dollar Broadway hit?” And the answer is yes, absolutely, and thank goodness he did. The popularity of Hamilton has sparked a huge and renewed interest in history, even among our young community of elementary students. Many of our kids knew the words to his songs and had seen the performance either live or recorded. At even the mention of a history dance performance, they were sold. Most of them.

Even the most well-planned and exciting project isn’t always going to engage all learners, at least not right away. When we began this dance project, we were met, much to our surprise, with a great deal of resistance from students who were reluctant to dance, or who flat-out refused. We often had five to ten students in each of our three classes hiding under tables or in the bathroom to try to avoid our weekly dance classes. In fact, up until the moment the curtains parted on exhibition night we weren’t sure that we would have a successful performance. Resistance, though, is not a reason to stop moving forward. While it is important for students to feel connected to and contributors towards their work, it was challenging to achieve this with five to eight out of my 25 students refusing to participate on any given day. The easy thing to do would have been to assign them “alternate roles” or “other access points” and press forward with dance for those who were actually interested. We discussed what types of jobs the kids who refused to dance could do, and in the end we decided that there wasn’t going to be a back-up plan. We believed in the power of dance to tell stories; it was a cornerstone of our project design. Allowing students to miss out on that experience would prevent them from a major portion of our learning goals. While it was a constant frustration to have to beg our students to participate, to repeat the same moves over and over again, to develop self-control over their bodies, we held to the conviction that it would be worth it for the final performance we envisioned in the end.

As teachers we carefully walk the line between recognizing what the behavior of our students is trying to communicate, and how to both acknowledge their feelings and gently push their boundaries. Sometimes students are simply not ready for what we are asking them to do. Sometimes they need to stay under the table (whether literal or metaphorical) a little bit longer, and that’s okay. In our case, we knew that the nerves our shy students were feeling could be coaxed down, and we had many whole-class and individual conversations about confidence, making mistakes and supporting each other in taking risks. And you know what? We ended up getting everyone out from underneath the tables eventually.

Over the course of the project we made a few key changes to our initial idea. We simplified the performance to encompass just the history of the Civil War. Narrowing the scope shortened the total performance time to about 20 minutes which was easier for everyone to manage. We broke up the history of the Civil War into four categories and assigned a different style of dance and music to each: enslavement and the Underground Railroad, the Union and Confederate armies, the Battle of Gettysburg, and Reconstruction. We knew we wanted the Battle of Gettysburg to be a whole-grade hip hop dance battle, but we let the students choose which of the other three dance pieces they wanted to be part of. This element of choice empowered many reluctant dancers. Each group choreographed their own dance piece (with the exception of the soldiers who learned a traditional Civil War era dance called the Virginia Reel) and the students’ ideas for choreography took center stage in each piece.

Our final dance performance wasn’t perfect. We had only two rehearsals in the High Tech High Mesa theater prior to Exhibition Night and the novelty of being in the theater gave the kids a level of energy we had hoped would dissipate and didn’t. We spent all night begging them to wait quietly backstage until their turn was up. Kids missed cues, even after multiple months of practice. Moves were mixed up, costume pieces were forgotten backstage and even despite this the final performance was the best the kids had done all semester. Families walked out in awe and many shared the same sentiments: “I had no idea he could dance like that,” or, “she didn’t tell us the dance would be so good!”

If I were to do this project again there is plenty I would change—this is how I know we were onto something with this work. A project that runs smoothly from start to finish doesn’t leave room for the human element of trial and error, rarely involves risk, and often has limited learning. Even with its shortcomings, this dance project did accomplish its main goal: we were able to take a group of 75 fourth graders and turn them into dancer choreographers who were able to tell the story of the American Civil War from four different perspectives. When you watch the performance you will see the story of Black resilience and their fight for freedom via the Underground Railroad. You will watch soldiers partake in a traditional dance that helped provide respite on the battlefield and improve their tactical footwork. You will witness the Union and Confederacy battle it out for their unwavering beliefs, and you will walk through Reconstruction as our country tries to heal from the deep wounds this war caused. As you watch the video of our performance, I encourage you to consider the importance of elevating non-white voices in history, the opportunity to build empathy through taking perspective, and the relevant and lasting impact our history has on our present and future.

Aguilar, E. (2010, April 8). How to Engage Young Students in Historical Thinking. Edutopia. https://www.edutopia.org/historical-thinking-skills-K-6